There aren’t many hotter labels on the planet right now than Fat Possum.

Just don’t let that fool you into thinking that the Mississippi company’s done things the easy way.

With the likes of The Districts, The Fat White Family, Temples and Seratones on the US label’s books in 2015, you might envision a slickly proficient A&R machine – one well-versed in corporately out-positioning its rivals.

Sit down with Fat Possum co-founder Matthew Johnson for any period, though, and he’ll teach you the error of your ways.

The way Johnson tells it, Fat Possum’s history has been a patchwork of missteps and last-minute glory ever since it set up shop 24 years ago.

It’s been a journey kept on the road by some fortunate happenstance, brilliant A&R decisions and serious leaps of faith.

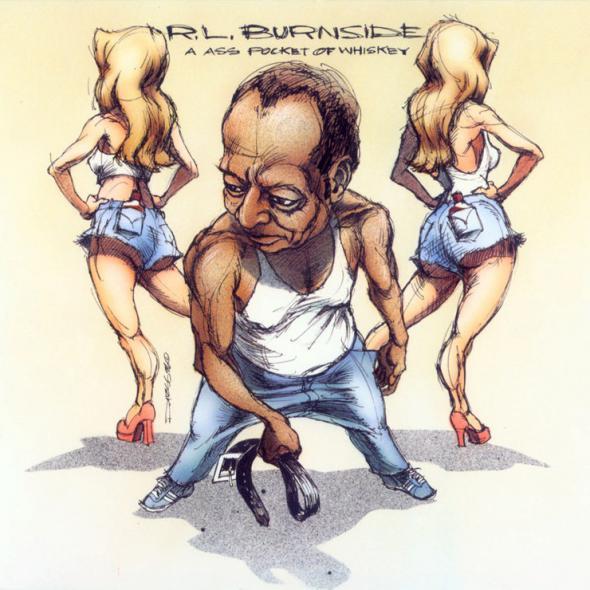

You’ll pick this up by glancing through Fat Possum’s back catalogue, which includes Modest Mouse, RL Burnside, The Walkmen and Johnson’s most famous signing, The Black Keys.

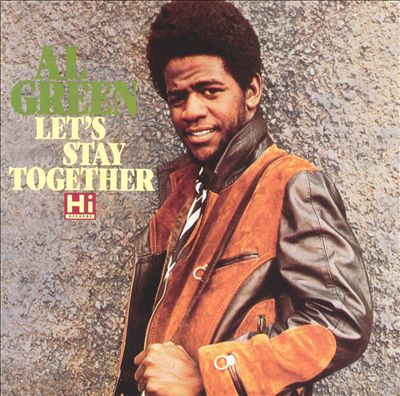

Amongst other Fat Possum assets, you’ll also find the classic recordings of soul legend Al Green – the product of a canny Hi Records acquisition from EMI – as well as the label’s very own vinyl plant, Memphis Record Pressing.

In typical Fat Possum style, this mini-factory nearly cost them everything – but it might just end up paying major dividends.

Below, [PIAS]’s Kenny Gates chews the fat with Johnson, and discovers how a record company once plunged into the financial blues kept the faith, leaned on its friends… and revived itself.

I came across Fat Possum for the first time in the early 1990s when you were going through Epitaph and we began distributing RL Burnside…

First we were with Capricorn Records. That was a disaster!

It ended really badly, on Music Row in Nashville.

We were in bankruptcy after that, and that’s when Brett [Gurewitz, Epitaph boss] got us.

He bailed you out?

Oh, totally. Things were happening pretty fast at Epitaph at the time, The Offspring had just exploded.

The only question Brett asked me before the deal was: “Who would win in a fight: The Incredible Hulk or The Terminator?”

I said The Terminator… and that I needed $175,000 just to keep the fucking lights on.

He gave it to me later that day.

How did you get started as Fat Possum?

We started putting out RL Burnside and Junior Kimbrough records in 1992.

We started putting out RL Burnside and Junior Kimbrough records in 1992.

And you began life purely as a blues label?

That’s what we began as, certainly, but pretty quickly we started getting into other stuff.

We were always a little bit different; even our touring was different.

You probably remember A Ass Pocket Of Whiskey [from RL Burnside, pictured], which came out on Matador – that was our first record.

“The only question brett asked me before our epitaph deal: ‘Who would win: The incredible hulk or terminator?”

We were in bankruptcy, so we licensed it to them.

RL was hanging out with Iggy Pop, Jon Spencer, all those guys. But we couldn’t put stuff out under our own name. We had tonnes of ‘cease & desist’ letters and shit!

We didn’t do anything right.

Why did you start a record label in the first place?

I didn’t think it was going to work. If I did, I’d have come up with a better name.

It felt like a joke: let’s just do this, and then move on to the next thing.

But now Fat Possum’s been going for over 20 years.

It’s so hard right now for an indie label. I don’t think it’s ever been harder.

Why is it so hard now?

It used to be that it was like a curse to be on an indie label; that if you had indie distribution, the band would go free. That used to be written in.

I guess the flipside back then was that there was so much more money.

“Guys at majors used to tell our bands: ‘Fat possum can’t give you the push we can.’ Now they tell them: ‘We’re just like fat possum.'”

Guys at majors used to go to our bands and say: ‘We love Fat Possum but they can’t give you the push that we can.’

Now they try to steal them by saying: ‘We’re just like Fat Possum. We’re indie like them.’

It’s crazy how it’s all flipped around.

Like how?

Look at Sony Red in the US. I think with all their independent labels combined they have a bigger [distribution] market share than any of the fucking major guys uptown.

Mumford & Sons, Jason Aldean and all that [independent] stuff – platinum artists that have been taken from zero, really, and developed without huge campaigns.

It’s kind of wild. It used to be that you couldn’t do that on an indie.

Brett was the first person to have a [US] No.1 record in something like 25 years [on an indie].

Since then, I get the impression that the management community are far more open to dealing with an independent than with a major.

Yeah. The gap between the worst record label and the best record label, and the worst distribution and the best distribution, has gotten so narrow now.

[video_youtube id=”frRjX0GQe1A”]

So what do you tell a band like The Districts; why should they sign to you and not a major?

Well, you have to sign them real quick [laughs]! It’s really hard to win that battle with the majors.

Every band says they don’t care, but when the money starts stacking up, they really do.

That [loyalty] shit can go out the window real fast.

If you go to a major, at least wind them up for a bunch [of money]. Or build on an indie and then go.

“The majors still have a lock on radio, whatever anyone says, even if it’s eroding.”

When The Black Keys left [for Nonesuch], for instance, as much as it killed me, we had like two or three [staff].

Now we have like 14 people so I feel we could go head-to-head with [Warner]. We couldn’t back then.

[The majors] still have a lock on radio, whatever anyone says, even if it’s slowly eroding.

I didn’t know what Nonesuch was. It wasn’t really a powerhouse at Warner, and still isn’t, really.

Now, Red can help you – and obviously you have a great partner in Europe…

Yeah! One thing that’s fucking awesome is that when we took the Al Green stuff from EMI [the Hi Records catalogue], that was huge.

Yeah! One thing that’s fucking awesome is that when we took the Al Green stuff from EMI [the Hi Records catalogue], that was huge.

We’re selling more Al Green records a month than they were!

They were doing like 400-500 and now we’re back up to 1,600-1,700. So things have changed.

We get our report card from Soundscan over here every week: boom, this is how good you are.

Why did you consciously want to sign blues artists in the beginning?

They were the best quality thing I could find and they were local. I wanted to do it differently.

These old [label owners] were making these blues guys go back to acoustic music and pretend like they were in the 1950s.

I wanted it to be more of a freak scene; I wanted them in the punk clubs, for it to move real fast and get out of hand. And to start as many rivalries as we possibly could!

What about signing The Black Keys – that must have been a very important moment.

I talked to Jack White a little bit and Judah [Bauer] from the Blues Explosion, who’d also done a two-piece.

There was a time when that wasn’t viable; it was like, ‘Get a fucking bass player.’

“There was a time that a two-piece wasn’t viable. It was like, Get a fucking bass player.”

The Districts now is a good example of how we treat acts. I hope they’re happy.

We try to give them whatever they want and stay out of their way.

Hopefully that belief will be repaid…

We’re comfortable where they are right now.

But there comes a spot where the indie labels are typically weaker – probably around half a million [sales], things can start to break up.

That’s when the majors, for the most part, really grind it out.

Probably the only people that have made it to that level are you guys and Red, maybe ADA.

But what’s important is that bands can still do great with 200,000 worldwide sales on an independent.

Fuck, yeah – we can do great with 80,000!

Did you ever think of selling the label?

Every day… oh, I don’t know. Maybe that’s not true.

Some days it’s uphill, you know?

We’ve been lucky to have the trust of some people I really admire. And getting the Al Green stuff, getting the Modest Mouse back catalogue, having The Black Keys early stuff; that’s been a dream come true.

We work really hard at this, I hope our bands see the value in us.

[video_youtube id=”ZutKlps1myA”]

It’s not unheard of for bands to be ungrateful about a label’s investment when things go right in their career. Do you feel frustrated by that?

No, I usually take their side!

It’s like, of course they don’t trust labels! We have nine bands on our desk, and they’ve got one – that’s it.

Indies have done such a shitty job so many times in the past and fucked things up.

One of my artists once told me: Kenny, you’ve got 20 bands, I’ve only got one career.

Exactly. We [as an industry] take that shit for granted. It’s a problem.

“Of course bands don’t trust labels! We’ve got nine bands on our desk – they’ve got one!”

Every bus that comes around the corner has a band on it.

So chances are, eventually, we’ll step into some luck.

What makes you decide to sign a band? Is it the tune, the attitude, the fact they’ll sell?

In the past I’ve signed stuff just because I’m super-lazy. I’ve stopped that now!

We’ve really focused over the last few years. We don’t sign so much anymore. We got smart.

If you treat the music business like a lottery, then your chances of winning it are… like a lottery.

I was going after stuff like, ‘Fuck it, I don’t need to own a label.’

I was flat broke when I signed The Districts, totally out of money. I went all in.

I decided: ‘If this band doesn’t work, I probably shouldn’t be doing this for a living.’

It was the same with Seratones. It was like: ‘Don’t let them leave the room until they sign.’

Fat White Family were so self-destructive, I had to have them.

I’m like a parent who loves the ugliest child the most!

You’re one of the hottest labels in the world as we sit here, but it’s happening as Spotify and streaming takes over. How do you feel about it?

I’ve got my fingers crossed. I mean, hopefully it’s going to work. It scares me.

Insanely enough, I drove with The Districts for ten hours recently, just to see if I could still handle it. I used to live in fucking vans!

“I was FLAT broke when I signed the districts. I went all in.”

I noticed there weren’t any CDs in their vehicle, at all. And I was like: ‘That’s finally going.’

I don’t even know who buys CDs anymore.

It frightens me that half our money comes from people I don’t understand. Do you buy CDs?

I buy vinyl. You just launched a vinyl plant!

It’s a big undertaking. If we’d have done our research, I don’t know if we’d have done it.

Sometimes as a business, it’s like we’re saying: ‘Our aim is to sit down.’ But then we have to chop up a tree, sand it into boards, nail them together and make a chair.

We did the vinyl plant, because the [market] just wasn’t consistent: every time we turned around, the rates were going up, we couldn’t get enough manufactured…

At Christmas, the shitty Government withheld like 3,500 Modest Mouse records that were back-ordered.

It’s like the Raiders Of The Lost Ark out there. Bullshit.

So let’s get this straight: you outright bought a pressing plant?

Ha, no! We bought a scrapped pressing plant, that was all wrecked.

We loaded it wrapped in plastic because pieces of it were falling apart. It was ragged out. And then we got this old guy to put it all back together.

Today, we have nine working presses.

[video_youtube id=”g_OV9v6hrak”]

We went back to the bank three times. And the bank was like: ‘Have you guys worked any of this out on paper?’ [Laughs].

It’s the same bullshit you get with bands! ‘We’re 90% done with the record, but the last 10% is going to cost twice what you’ve already spent.’

The infrastructure you need is crazy; a huge boiler, steam pipes… these things don’t come with a manual.

So it’s working now?

Oh yeah, it had to! Fat Possum put up all the money. There was no other option. I think I spent Christmas Eve fixing it up.

Hopefully it’s going to work; hopefully this vinyl thing is going to grow for at least another three to five years.

Everyone we work with is going to want their records made, right?

It was so frustrating before to have something that was actually selling, which we couldn’t supply.

Why did you split with Brett and Epitaph?

They kind of fell on tough times. They felt they were putting in more than they were getting out of [Fat Possum], and perhaps we felt we didn’t need their help anymore.

Brett was about as good a business partner as we could have had. It ran its course.

Do you remember the first time you saw The Black Keys live?

Yep, they played a shitty bar in Oxford, Mississippi.

Yep, they played a shitty bar in Oxford, Mississippi.

I think we signed them in 2003 or 2004 – you have to remember it took ten years for them to make it.

They didn’t explode until 2011.

Well that’s testament to you sticking with things in the long-term.

I think so. Building for years puts a foundation under a band that they can’t get from one big radio hit or a car commercial.

“It happened with modest mouse and the black keys: things that heat up slowly also cool down slowly.”

It happened with Modest Mouse, it happened with the Keys: things that heat up slowly also cool down slowly.

Some people have said that Moby’s huge Play album was inspired by RL Burnside. How did you feel about it?

Everybody grabs something from somebody. I don’t feel it’s stolen at all.

I suppose he beat us at our own game.

Have you got a vision for the next ten years on the label?

Oh no.

What about the next ten days?

That, if you give me a minute, I can probably come up with [laughs].

We need to make sure we’re with the right partners and going in the right direction.

If we do that, we’ll be fine.

I take comfort in the fact that, besides pesticides, entertainment is still America’s biggest export.

And weapons, of course.

We’re not allowed to deal in weapons. If you want to make money, it’s all about pesticides.

Would you consider yourself a hopeless romantic?

No. I’m a happy-go-lucky nihilist.

I’ve seen it not work out so many times – but, you know, it could be worse.