From modest beginnings, Tommy Boy Records became one of the most iconic music business names in rap.

From modest beginnings, Tommy Boy Records became one of the most iconic music business names in rap.

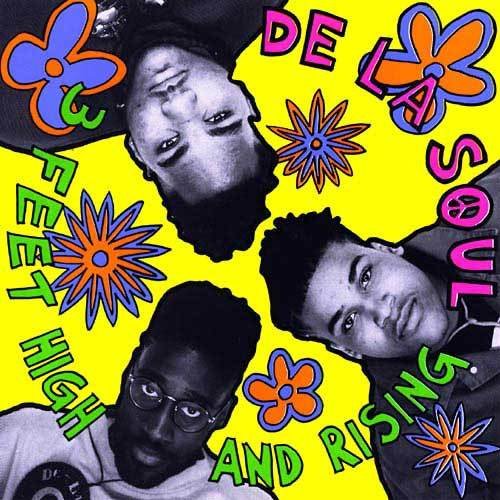

The label was responsible for putting out a string of hits in the 1980s and 1990s, including House Of Pain’s Jump Around, Naughty By Nature’s OPP and Coolio’s Gangsta’s Paradise – as well as De La Soul’s seminal 3 Feet High and Rising.

Behind the scenes, founder Tom Silverman was additionally responsible for creating one of the most influential music business events – the New Music Seminar, in 1980 – which continues to take place annually in New York to this day.

NMS stoked a natural curiosity in the music biz’s evolution in Silverman, and in 2016, he’s well regarded as a sage about the future for independent labels.

Silverman started Tommy Boy after co-founding a popular newsletter for DJs, Dance Music Report, which forged its reputation during the disco boom of the late Seventies – an experience which taught Silverman how to keep his ear to the underground.

[PIAS]’s Kenny Gates sat down with Silverman to delve into Tommy Boy’s history – including his decision to sell the label to Warner Bros – and ask about where he sees streaming taking the recorded music business…

How did Tommy Boy begin back in 1981?

The Dance Music Report was in debt by around $50,000 at the time.

My partner on the newsletter, Scott Anderson, and I had set up a one-stop to distribute records – mostly singles and 45s to record stores.

So much cash was coming in that it seemed very profitable. Scott approached me about taking my share in the one stop.

I said: ‘How about you pay half the debt, I’ll keep the newsletter and you keep the one-stop.”

“We looked at sugarhill records in 1979, who sold millions of 12-inches.”

Pretty soon I got the Dance Music Report’s debt paid off and started becoming profitable.

At the same time, I’d been researching the idea of starting an independent label.

I’d talked to the independent labels [in dance music] and they weren’t necessarily that smart or that forward-thinking. I thought I could do as well as they could do.

We looked at Sugarhill Records in 1979 and we saw Rapper’s Delight come out and sell millions of 12-inches.

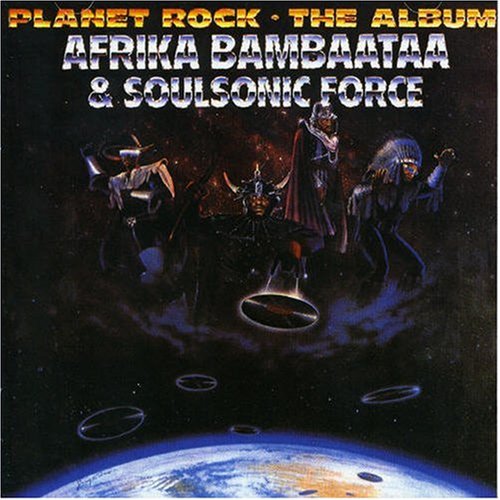

So we started a label focused on the 12-inch business – a new format that was exploding, just like streaming today. We started Tommy Boy and when we signed Afrika Bambaataa, our first artist. We didn’t even have album rights, only 12″ rights.

Am I right in thinking you took on Billboard with the New Music Seminar when you launched it?

Am I right in thinking you took on Billboard with the New Music Seminar when you launched it?

Billboard had been running the disco forum since 1978 – a big conference with 1,200 disco DJs coming together.

People spent a lot of money there and there were crazy amounts of drugs going around. Casablanca Records and TK Records would lock out the top two huge penthouse suites.

“There were crazy amounts of drugs going around… the parties were like orgies.”

Both labels were run by gay guys and their parties were like orgies.

Even though we’d run our newsletter for a couple of years, we were straight and they didn’t want us there; the guys on the door just wanted to make sure everyone coming in was cute and available!

We put our [event] up against theirs in 1980, which was the same year theirs began to fall off. They blamed us but we only had 200 people – and most of them weren’t the kind of people who’d go to their event anyway. Then ours just got bigger and bigger.

How did you finance Tommy Boy in the beginning?

How did you finance Tommy Boy in the beginning?

My parents lent me $5,000.

They’d lent me $5,000 to start the newsletter, which I don’t think I ever paid back.

But with Tommy Boy, within a year I was able to pay them back because we had a hit record – Afrika Bambaataa & The Jazzy Five’s “Jazzy Sensation.” It sold about 35,000 12-inches.

How did you come across Afrika Bambaataa?

I was writing an article for Dance Music Report about this new style of music called Break Beat coming out of the Bronx.

I went to this record store called Downstairs Records in the subway on 6th Avenue and 43rd St.

They’d opened a new room which was almost like a closet, and on all the walls were weird records; The Eagles, Dennis Coffey, The Incredible Bongo Band, Kraftwerk.

Then there was a line in the hallway about 15ft long of young black kids waiting to buy these records.

I asked them, how do you know what records to buy? And they said: ‘We buy what Bambaataa plays.’

I went to the Bronx to hear Bambaataa spin and he was doing shit that blew my mind. He was playing Kraftwerk and James Brown next to each other; Sly and The Family Stone next to Billy Squire.

He had two DJs next to him and when he wasn’t spinning he was giving them records and telling them what to play. I’d never heard anything like it.

“I’d never heard anything like it.”

I said, ‘Do you want to make a record with me that sounds like that?’ I hadn’t even started Tommy Boy – this was in 1980. He said yeah. We went into an eight-track rehearsal studio and made a demo. About three weeks later I played it for Arthur Baker who said: ‘I love this, can I produce it?’

After Arthur Baker had produced Jazzy Sensation in 1981, we went in with [Bambaataa’s] second record [Planet Rock] and that was a runaway hit – it did 620,000 12-inch sales. At the peak we were selling 30,000 – 40,000 12-inch singles a week.

Why didn’t Bambaataa ever become as big as your other big stars?

We didn’t have a contract with Bambaataa that allowed us to make albums, so we had to negotiate an album clause, but his lawyer was really difficult.

It took two years for us to get a contract finalized, and after those two years, when we put the album out, nobody cared. We needed to do it when the record was hot.

We sold 620,000 12-inches when most people didn’t even know what 12-inches were. We would probably have been able to sell a million-and-a-half or two million albums if we’d been allowed to put an LP out soon after Planet Rock. And then I got sued by Kraftwerk!

Explain…

It was publishing. Everything was re-played [on the record] but there were beats and melodies on there that sounded like music Kraftwerk had done.

I didn’t know the legalities of copyright very well, and I learned the hard way. Then I hired a lawyer!

Was Tommy Boy a pioneering label?

Definitely. Planet Rock was the first record to use the 808 drum machine, and we were the first ones to really clear samples for records.

We experimented with the recordings process, the manufacturing process. We looked at everything that was and thought: ‘What if we tried it a different way?’

[video_youtube id=”9lDCYjb8RHk”]

How could you be so influential in hip-hop with such little startup money?

We were able to sign rap groups for very low prices because it was just us and another few New York indies. But by the nineties, the majors got into it and drove the price up.

They were paying $20,000 per track just to the producer – which was what we’d practically paid for the entire album before.

“It cost $300,000 – $400,000 just to work one hip-hop single at radio in the mid-nineties.”

The majors also put mix show [radio] DJs practically on retainers – so there was payola. Pretty soon you had to pay $100,000 just to work a record on the mix show… to even see if you had a record worth going to radio with.

At black radio you’d pay another $100,000 and then Top 40 you’d pay another $150,000.

So it cost $300,000 – $400,000 just to work one hip-hop single at radio in the mid-nineties.

Payola! Did you used to do that?

Sure. We’d get the radio add on a Tuesday, and then if they played the [track], we’d FedEx the station $300 the next day.

That’s back in 1981 and 1982. You only had to do it with two or three stations to get a test.

Once the record was legitimate and was reacting you didn’t need to pay anymore.

Nobody wanted to play rap records at the time. Black radio hated rap, they thought it was offensive and in Europe it was even worse – especially in England. It was anti-rap.

[video_youtube id=”6xGuGSDsDrM”]

Did you have a philosophy as a label the time – did you have a belief?

We were trying to listen to what the street was saying and trying to follow its trends; fashion trends, music trends, cultural trends and build them into everything we did.

“We were trying to listen to what the street was saying.”

This whole idea of black music and white music coming together was really exciting to me; it was a microcosm of the way I wanted to see the world.

That’s quite a romantic view of things.

I guess so. It’s idealistic, at least. What else should we aspire to? Peace and love, rainbows and happiness. What the fuck else is there?

What’s your purpose? Where does your fire come from?

At this point, it’s to be liberated from all of these thousands of programs we’re all running which is who we think we are – but it’s not. If we wiped out all the programs, who would we be?

My purpose is to discover that – who is the spirit of Tom Silverman before the programs made this guy?

“How do you get back to your pre-programmed state?”

When you have a new computer, it’s very fast but when you’ve had it for two or three years it really slows down – the hard drive is full, the RAM is full, it’s clogged up.

We’re that way too – our minds are that way. And as we get older we get hunched over with the weight of it.

How do you get back to the pre-programmed state?

One of the biggest hits in Tommy Boy history was Gangsta’s Paradise from Coolio…

That was the second album from Coolio. He did an album before that which went platinum – the only act we had that did two platinum albums.

Gangsta’s Paradise was in a movie, Dangerous Minds with Michelle Pfeiffer, and also put Coolio in the trailer and ads for the movie; they actually put Coolio in the ads even though he wasn’t in the [film].

The soundtrack went triple-platinum, and [Coolio’s] album, which also had that song on it, did three million – so that song actually sold six million albums just in the US.

[video_youtube id=”ryCpg8f45gc”]

Why did you sell a chunk of your business to Warner in 1986?

In 1985 we had a drought.

We had nine or ten employees and we had a cash flow crunch; we owed the pressing plant hundreds of thousands of dollars. At that point I felt like we needed to raise capital.

“Pop radio was controlled by five powerful guys. Only the majors had access.”

Plus we couldn’t get our records played on pop radio.

Pop radio was controlled by five powerful radio promotions guys across the country and they had a lock on all radio play. Only the majors had access.

Exactly how much did you sell of your company in that deal?

Exactly how much did you sell of your company in that deal?

Exactly 50%. The idea was that we would be able to keep our independent company: they could put the albums out and we could put the 12-inches out.

I had to go back a few years later and renegotiate our deal and say we wanted a veto right on their ability to pick up the albums – the margins weren’t enough.

They said okay to that, so we put De La Soul and most of the following albums through Tommy Boy direct independently.

In 1986 when I made the deal I actually thought we’d get access to their radio promotion but that was when there was a giant payola scandal so Warner Bros stopped using all the independent promoters!

But why sell in the first place?

But why sell in the first place?

I wanted to pay the pressing plant, and I got $600,000 in cash to pay off debts, which was some bullshit.

But it actually turned out to be a great thing because I became a Senior Vice President at Warner Bros – I got to learn what the majors do, in the belly of the beast.

“Other than money and scale, the majors don’t do anything the indies don’t.”

Guess what? Other than money and scale, they didn’t really do anything the indies didn’t do.

In fact they weren’t as innovative; they didn’t try things because they were afraid to and they were so bureaucratic, they spend a ton of money on politics within their own company.

You eventually sold the whole of Tommy Boy to Warner. Do you regret it?

No. I made a lot of money. Entrepreneurs tend to be very attached to their businesses and very often do not sell at the right time when they have opportunities to cash out at ridiculously high prices.

[Being too attached] is one of the “programs” we have to work on getting rid of; entrepreneurs especially.

The entrepreneurs I really admire are the ones who stay detached and take the big fucking cheques. It’s about selling out at the right time.

“The entrepreneurs I really admire are the ones who stay detached and take the big f*cking cheques.”

You get the money… but do you keep the purpose in your life?

Clive Calder got $2.6bn [for Zomba]. Does he really regret not being in the music business anymore? He works with charities in South Africa, and can give money and invest in [new ventures].

To me, investing in entrepreneurs is like investing in artists, and investing in artists is like venture capitalism – it’s a high risk gamble and something I would be interested in doing.

On the subject of A&R, you have a special view. Is it true you don’t believe in it?

Well, I believe in A&R, but I don’t believe in the old style of A&R.

My investment in A&R [at Tommy Boy], which was close to $10m over a decade, didn’t bear fruit.

“Whenever indies try to be like majors, we lose.”

Between what we paid to sign and develop each artist – hundreds of thousands – plus the A&R person and their expense account, each [A&R exec] cost us a million dollars.

Whenever indies try to be like majors, we lose. And I was trying to be a major. We had 110 employees in New York alone, it was crazy.

You’ve become very into data in recent years, and are something of an analyst of the industry. Why does a music man like you love data so much?

Data is a kind of new drug, and any kind of new drug helps you see things you can’t see when you’re sober.

When you’re sober all you have is your eyes and ears – which in our world is what you can read in Billboard or what’s on the charts.

Everyone else can see that – so it doesn’t give you a special way to find a new artist or a new way. Data helps identity opportunities we might be missing.

What means more to you – New Music Seminar or Tommy Boy?

Tommy Boy. NMS is great; it’s great to get people together and invent new things – and change the conversation from units to ARPU, from sales to behavior. The music industry needs things like NMS, where people can change their paradigm.

It’s not the record business anymore; it’s the attention business. And the question is, how do we monetise that attention better than we were able to monetise just selling records?

Who are your mentors?

Seymour Stein’s always been a mentor, and Mo Ostin. Morris Levy was a mentor, although I didn’t get as much time with him as I would have liked.

Ahmet Ertegun was a mentor, and so was Chris Blackwell too.

I’m forgetting one… more recently, Quincy Jones. There’s so much you can learn from the trailblazers who went before. And there aren’t that many of them.

What are the mistakes you have made in your career?

But what’s a mistake? I believe that mistakes are what move us forward.

Selling half the company to Warner Bros was a mistake in some ways but I also learned a whole lot from that deal.

The main lesson was that the emperor has no clothes: indies have an inferiority complex and think majors have some special sauce we don’t have. Not true. They just have money.

What does the future hold for independent labels?

I think independent labels are going to grow because the majors are painting themselves into a corner. The majors’ business model is going to go away when radio goes away – and radio has to go away eventually.

When every car is connected with Pandora, Spotify etc. and things open up, radio will fall – it will no longer be the main way music breaks. And at that point the majors will have a lot less meaning.

What about the future of the music business at large – are you optimistic?

What about the future of the music business at large – are you optimistic?

I love subscription streaming. If we can just get to 300m paid subscribers instead of the 60m we have now we’ll be in a much more comfortable place.

Then we can aim for 600m or even a billion subscribers, because in 2020 there’s going to be 6.1bn smartphone users around the world.

Thinking that we can get 15% of them to subscribe at some price – even if that’s $2 a month in South America and China – doesn’t seem crazy.

$2 a month would be $24 a year, from which $16 would go back to the music industry, which is more than we’ve ever made from these countries, and you can already see it happening.

I’d love to see a three-horse race: Spotify vs. Apple vs. someone else, maybe YouTube Red.

Is YouTube the enemy?

They’re not the enemy. They just have a philosophy that depresses the value of music and will slow the acceptance of subscription worldwide, especially in the developing world.

YouTube has just offered a $0.99c three-month trial to [subscription service] Red, which is very aggressive and good to see.

There are a lot of negative people out there, who say: ‘Spotify can’t be profitable on a 30% margin.’

I think that’s all bullshit. Supermarkets are profitable on a 3% margin, with lots of expensive real estate. Spotify hasn’t reached a critical mass yet.