If you want to know how particular Christof Ellinghaus is about quality, you don’t need to listen to any of City Slang’s records.

If you want to know how particular Christof Ellinghaus is about quality, you don’t need to listen to any of City Slang’s records.

Ellinghaus, one of Germany’s most acclaimed record executives, is a co-owner of a wine bar on Große Hamburger street in Berlin – and his finickiness about the standard of its offerings speak volumes.

“We got all these awards for the concept as we launched,” Ellinghaus tells The Independent Echo.

“I was like, ‘Concept?’ There wasn’t a concept. Berlin just needed a bar where you could drink really good wine at 11pm and listen to Yo La Tengo – not new jazz.”

You won’t find a great deal of new jazz influence in the catalogue of City Slang Records, the Berlin-based label which Ellinghaus has built up since the early 1990s.

City Slang cemented its taste-making reputation by bringing seminal alternative American bands – including Sebadoh, Hole, The Flaming Lips and Built To Spill – across to Germany (and further into Europe), typically through licensing deals.

In more recent years, its sonic palette has broadened, bringing through the likes of Arcade Fire, Lambchop, Calexico and Caribou – while maintaining a philosophy that puts the artist at the centre of its universe.

Not that Ellinghaus is a soft touch.

As he explains to [PIAS]’s Kenny Gates, ‘the German in me’ always demands the best – with no compromises…

What got you into music in the first place?

The feeling music stirs up in you! That’s what it’s all about.

It can invigorate you. It can take you so high and so low. That fascinated me.

The rest just sort of happened. I never went into this with a business plan. Most people didn’t, right?

We didn’t know what the words meant when [PIAS] started! You started as a tour agent, right?

I had written for this fanzine – The Glitterhouse.

I wanted to be a music journalist when I came out of school. My hometown was a small village in the middle of West Germany called Beverungen, which also happened to be the home to Glitterhouse Records, which was a fanzine before it was a label.

I moved to Berlin and became the local distributor of this fanzine in the record stores. They called me and asked if I could tour-manage The Chesterfield Kings – one of the bands that we’d written in the fanzine about. It was pure ’60s garage rock, played in the ’80s.

‘Do you want to tour manage this band? You drive them around Europe and at the end of the day you collect the cash.’

I thought I could probably do that.

So how did you get into running a label?

So how did you get into running a label?

Two things came together. I was booking all of these bands, working with Yo La Tengo, Lemonheads, Mudhoney, Nirvana, SoundGarden, Flaming Lips – I was mostly the German, sometimes the European, booking agent.

And then The Flaming Lips’, Wayne Coyne, said to me: “We want to come back [to Europe] but we need a label to release us and we don’t have one right now. Can you help?”

They were signed to Enigma in the US. Wayne sent me a cassette – this was 1988 or 1989. I was playing the cassette over and over thinking it was the best record they’d ever made.

At that time, a German indie label called Vielklang – a very German indie label! – had asked if I wanted to run a [sub-label] for them.

Initially, I said no: my whole thing was that my taste was somewhere in the US, not in Germany. That was my specialty.

But then I got that Flaming Lips record, so I went back to them and said: ‘Hey, I can do this for you… but it’s got to be my own musical ideas, and I’ll come up with my own name.’

They had the money ready, and said okay.

I called Wayne and said: ‘Can I put the record out?’ And he said: ‘Well, we’re just about to sign to Warner Bros., so this is our last record on an indie. So it kinda doesn’t matter, but we trust you – you can do this!’

And that triggered me starting a label. It was late ’89, early ’90s as it came together.

Then came The Lemonheads, Yo La Tengo… people were just, ‘You’re starting a label? Here’s some music – please put it out!’

The first release I actually did was an EP From The Lemonheads, Favorite Spanish Dishes.

Then [Domino founder] Laurence Bell turned up and said: ‘I love that band and this release, can I put it out in the UK?’

That was his Roughneck Recordings. So we share the same first release.

How did the Warner Bros deal affect your Flaming Lips agreement?

To get the Flaming Lips album licensed out of a situation in the US, where Restless/Enigma were just going out of business, it was a very complicated ordeal.

It’s a bit of a paradox – a Germany-based label releasing licenses from America in Europe… including the UK.

Not just a paradox – a tough sell! In that situation, you need someone, an artist, to kick open some doors for you.

Who did that for you?

Hole. Courtney Love’s band.

I was spending quite a bit of time in New York, and I hung out with all of these US bands, which was always great because I’d come back to Germany with more new friends, more bands and more work to do.

In March or April 1991, my friend Janet Billig, who worked at Caroline Records at the time, said: “You should meet this girl Courtney Love – she’s making a record with Kim [Gordon] and Don [Fleming].”

I met her and Courtney was charming and loud and abrasive. We all knew right away that she had something going for herself.

Someone else in Europe was interested in putting the record out, but I was there first – they played it to me and it was amazing.

I would go back home to Germany, and every morning at 11am – when it was 2am in LA – I’d get a call: ‘Christof! How’s my record doing?!’

So the record that really put us on the map in the UK was [Hole’s] Pretty On The Inside, with [single] Teenage Whore – really great noisy stuff.

[video_youtube id=”hPAoTw8w6B0″]

Was she with Kurt Cobain at this point?

They didn’t even know each other. I had booked Nirvana in Germany and been friends with those guys for two years.

On the eve of Courtney’s first press trip in Europe, they met in Chicago, and she swiftly moved from Billy to Kurt one evening – and landed in Berlin the next day to tell me all about it!

She was really something. She is really something.

It was my impression – and I might be wrong – that you seemed to compete a lot with Domino in the beginning…

In the very early days, it was all about Lemonheads, Sebadoh – things like that – we [would be into similar things] and we would find an arrangement.

I always liked Laurence [Bell]. Maybe he was that bit more competitive than I was, I would say.

Honestly, I never really developed much of a sense of competition.

What?!

I’m a hippy at heart!

But I perceive you as quite an aggressive person…

That’s the German in me!

You started as a German record label competing with the Brits, you had to be competitive! Otherwise, how did you manage?

There was a mutual interest that Laurence and I had in the same music. Then our tastes moved into different places, so we weren’t getting in each other’s way so much.

And then… he took off! Come on – he’s like a gazillion times more successful than I am now.

He’s like a proper force to be reckoned with. Which I admire, but – I’m not so sure if I wanted to be… I mean it would be great to be in that position, but he also has to play the superstar game now which I’m not so interested in.

Commercialism for me, when it happened, it kind of just happened. It was the art, the artists, the bands that made that happen.

We can only help them along. If Caribou puts out four records and they each do 5,000 or 10,000 albums, and then one does 100,000, that’s not because I’m a genius – it’s because he’s the genius and he’s made made a record people want to hear. We can only push the right buttons to help it along.

If that happens on my label then I’m eternally grateful, but I don’t plan on it.

Laurence – and you [PIAS] to a degree – are now in the business of having to plan these things. And to plan these things in this day and age is really fucking hard.

[video_youtube id=”sLrOg1pvM40″]

In what way?

Forecasting. ‘Okay, this sounds super commercial’ – and then it just doesn’t connect. It happens all the time.

You’ve answered my question about Domino, but how did you forge your identity as a label out of Germany. It’s quite extraordinary to see how you’ve become almost the English label from Germany…

I don’t know whether to take that as a compliment…

It’s meant as one!

Thank you. The answer is pure luck – running into Courtney Love and then grunge happening. And maybe me not being a businessman.

In 1994 Geffen showed up and said: ‘We’re going to buy Caroline out of their whole contract.’

And then they called me and said: ‘Hey, we want to buy you out too.’

I called Courtney and convinced her that it was not a good idea to be in a major system in Europe – even though it might be different in the US and [Geffen] needed her, because Nirvana had happened.

I was able to talk them into letting me put out the second Hole album, Live Through This, and not go through MCA or whatever [the Geffen company] was over here.

That’s not being a businessman – that’s being someone who artists say: ‘Okay, we like this guy – or at least trust this guy.’

People trust me, and I think that’s important.

So who are your mentors – who inspired you to do this?

There’s Reinhard Holstein, whose started Glitterhouse Records in my hometown. He taught me about music, when I was getting out of puberty and jazz rock – ’70s noodly stuff. Reinhard introduced me to punk rock, new wave and pretty much everything else.

Later, in 1992, I bought City Slang out of Vierklang. Over the course of two years, I [realised]: Erm, I’m doing everything and you guys are doing nothing, yet I get the calls for the bills that aren’t paid.’

I partnered up with somebody who died one year later – and that guy was instrumental because he was a numbers guy. He taught me that you’ve got to get a system for the numbers – he injected something economic. Klaus Unkelbach.

Internationally, it’s been people like Corey Rusk from Touch & Go, the Sub Pop guys who were a total inspiration for me. Jonathan and Bruce were such cool dudes. They were running a business – but a business with attitude.

Then Gerard Cosloy and Daniel Miller – those are people I look up to and think, ‘Wow.’ Artistically as well as attitude.

Initially I just very much copied Glitterhouse in terms of setup: ‘Who’s your distributor in the UK? Who’s your PR?’ etc. I had no idea what was happening.

When and how did you become the head of Labels Germany?

Labels France started up and approached me. And they’re smart, so they were saying: ‘When’s the second Hole album coming?’

They were all over me to license the Hole album, and I was under pressure – there was Geffen, videos, grunge was happening. Everyone expected it to work.

[Labels released the Hole album in France and] did okay – they sold 100,000 or more records there.

Some time after Live Through This, they came back and said: ‘You also do Smog and this other stuff we like – we want to do a label deal with you.’

At the time, they had Beggars and Mute – I thought it was going to be in good company. That’s when we ended our deal with you ([PIAS]) and began with them.

And that’s when that French wild man Emmanuel de Buretel entered my life…

What are your memories of working with Emmanuel back then?

I was ushered into his office whenever I was in France. He was always saying something erratic and interesting and I’d leave and say: ‘What the hell was that all about?’

And I’d be told: ‘That was the boss of Virgin, I think he paid you a compliment!’

He started sweet talking me as early as ’97 or ’98.

Then in 1999 [City Slang] wasn’t doing great and I was going through a bit of a crisis – I didn’t have much we were excited about.

I met Emmanuel in Stockholm at a festival and he said: ‘Okay, I’m starting Labels everywhere – you want to be a part of it or not?’

So we did a license deal: City Slang was licensed to a company [Labels] that I would be helming in Germany. I thought that was pretty smart – I wasn’t losing complete control.

I thought Labels was, initially, an amazing concept – using major money to put interesting music on the map and being successful.

For some of my bands, The Notwist, Calexico and Lambchop, it’s been instrumental in growing them.

But then came the new management [at EMI] – Levy and Munns.

De Buretel was ousted, Labels was melted down – it didn’t make any sense anymore.

[video_youtube id=”g_gfQ9CssLA”]

So when EMI bought Virgin it all went belly up…

Yeah. The problem was that by that time, we were hugely successful with Labels in Germany – putting out cool music. We were hot property.

Cologne [EMI central] was all about Grönemeyer, Robbie Williams and breaking Coldplay, but otherwise probably losing money – a very old-fashioned German record company.

Udo Lange [Head of Virgin Germany] hired me initially; well Emmanuel got UDO to hire me, and introduced us at a big meeting in Berlin. I couldn’t get a word in all afternoon; these alpha males all just kept talking and talking.

I came home to my wife and she said: ‘How was it?’

I said: ‘I don’t know… I couldn’t get a word in.’ And she said: ‘Oh, then they must have loved you!’

When Levy and Munns took over, they ended Labels.

Then they came to us and said: ‘You can take over Virgin [Germany] in Berlin… Either you [close] Munich, or Munich will [close you].’

So you either had to kill off their people or your people – that was the choice?

Yes. I was made MD of Virgin Germany, with Tina Funk.

As a result, we had to close down the Munich office.

That was never the job I wanted in music: to go and fire amazing people who had worked in promotions for decades. I made sure Berlin was set up for my people, and then three months later I quit.

What was it like working for a major label?

I had every experience you can imagine in a major label condensed in that time, from way too many meetings to flying around the world attending MD’s conferences where they would make an entire ballroom full of their MDs chant the words ‘cash management’ as some kind of mantra. Totally bizarre.

‘Cash. Management! Cash. Management!’

Wow. What were you thinking when that was happening?

I was thinking: ‘Where the fuck am I? What sector is this?’

Those four years of major labelism in my life was a big learning curve.

Up to that point, I had done everything myself.

What did you learn?

What I want and what I don’t want. How to treat people. And that these companies are out to make money and I’m out to make art.

My label had always had one mission: to become a home away from home for all these American bands.

For the big corporations, it’s all about the numbers. For me, the art comes first.

I’ve always had a problem with people telling me what to do. And for three of those four years, people didn’t tell me what to do; I figured it out.

Then in year four, people started telling me what I ‘should’ be doing, so I was out – back to what I want to do.

The art comes before the chart…

Absolutely. If the art even hits the chart!

Indie labels are to this day started up by young people on kitchen tables with a passion for music.

That’s different than a tech startup which is hoping there might be venture capital funding soon.

Did you know you have a nickname?

Erm…

‘Pissed off Christof’…

Well at least it rhymes nicely. It’s true that I get emotional when I think something’s wrong – when me, my label or my bands are being treated badly.

I haven’t had a reason to do that for a while.

Now I’m 52, I’m probably in a different space than I was ten years ago. I think – I hope – I’m more mellow.

Well by nature an independent label doesn’t like to be told what needs to be done. They are also very passionate, but have a complex of inferiority – while hating that they have a complex of inferiority…

That all matches. That’s me!

It’s all of us! I think paranoia helps us survive – the worry that everyone’s out there to fuck us…

We don’t trust anyone.

What makes you annoyed these days?

The thing that really drives me up the wall is when a very inexperienced manager is looking after a band with potential – and getting in the way of them going all the way.

People have always said I’m very straight; I don’t mince words and I tell it like it is. It’s probably a German thing.

I love Germans, the way you have balls in global politics – but also in our industry, like the way GEMA has told YouTube to fuck off. What is particular about the German market, do you think?

I think it’s falling apart at the moment. Now is the time when, it feels to me, the physical market is [declining].

I don’t have a clever explanation for why the [physical market remains strong in Germany].

I’m no analyst, but Germans are value conservative and more stubborn, maybe, in their pissed off-ness!

We also have the most fucked up, complicated radio situation of any country on earth. It’s dislocated, it’s federal, it’s 90%+ major label.

What’s your view on YouTube?

In hindsight, we can only thank GEMA for putting their foot down.

Now people are realising that as we try to grow the streaming market, it’s being hindered by this company who’s doing exactly the same [as Spotify] etc. – yet it pays out a fraction of what the total streaming market pays.

The phrase ‘value gap’ is very nicely picked. The streaming market is in a very difficult phase, and windowing is driving people back to piracy.

Drake, the most streamed artist on Spotify puts his record out exclusively on Apple Music? That can’t be good.

What is the biggest challenge for the independent music community?

What is the biggest challenge for the independent music community?

The amount of music being released. No-one can do anything about that.

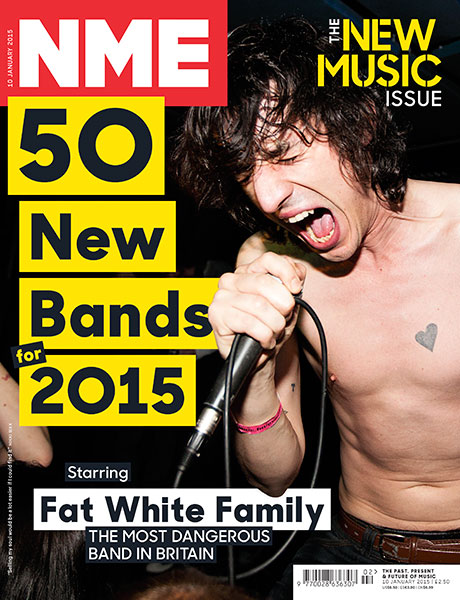

It’s not designed or decided in NME anymore who’s going to be a great artist – now it’s decided by a whole, weird almost uncontrollable mass of voices.

How many hype bands have shown up, and then album No.2 comes and they disappear?

That’s the biggest challenge. In the ’90s and 00s, you could build a band up slow.

Then we can talk about radio being blockaded, and neighboring rights income being blockaded – because a bully boy is sitting on it, saying: ‘That’s all mine.’

That’s a huge problem for the independent community. It’s really troubling to think that because of the screwed up radio situation most of the [GVL income] is going in one direction.

GVL is getting there, and they’re on a very good track. But it’s also very complex.

The fundamental problem is that everything in Germany is based on radio minutes, even private copying [levy] and so that mostly goes to [the majors] as well.

What’s the biggest mistake in your career?

Honestly, the indie labels who thrive and do well have built up a catalogue.

The fundamental flaw of my business is that it’s built on licenses, and [those deals] are for a limited amount of time.

I could have built something up to leave to my son, but if I close the door on City Slang, there’s [not many copyrights] left. But I also strongly believe in artists eventually owning their own art.

What has been your proudest moment?

When a band really comes through and I was there from day one.

I saw Kurt Wagner from Lambchop sell out the Royal Albert Hall.

That guy, to this day, is one of the greatest artists I’ve ever come across because he just keeps reinventing himself.

Are you still enjoying it?

Yeah! I love my job, and I love my life. I thrive on great music, it gives me endless kicks. Plus I have a wonderful family.

In artist development, sometimes you throw money into something and it just doesn’t go anywhere.

You’ve made a mistake, it was too early, something wasn’t right.

If you’ve got an amazing record with an amazing live show and an amazing story, you’ve got everything – if just one is missing, it can all fall apart. They’re like three pillars to a Roman temple.

That makes me frustrated sometimes – I just wish it was easier!

A you a romantic – an idealist?

A romantic? Probably not. But I’m a huge idealist.

The reason I got into music was an admiration of people who really had something to say.

The whole idea was: ‘This is amazing. Let me help you.’ And it still is today!