On March 30, Lord Huron’s The Night We Met was, commercially speaking, nothing to write home about.

In fact, it was a song that seemed to deliberately shy away from any pretense of becoming a streaming hit.

The very last track on the Los Angeles indie-folk band’s second LP, Strange Trails, it was a delicate acoustic ballad – a far cry from the high-energy hip-hop and EDM found at the top of your typical Spotify chart rundown.

Then, on March 31, the controversial teen suicide drama 13 Reasons Why (pictured) arrived on Netflix.

The Night We Met soundtracked an emotional scene at the heart of episode five. (It involves a slow dance, but we shall spoil no more.)

Less than 24 hours after the show premiered, The Night We Met had been streamed 2m times in the US alone.

To date, its playcount just on Spotify has soared above 118m.

To put that number into context… it’s around 25m plays more than Justin Bieber’s latest single.

[video_youtube id=”KtlgYxa6BMU”]

The fact that a great sync moment can change an artist’s career is nothing new, of course.

The big difference is that today, when one connects, it really goes global – fast. And, as a record label, you better be ready to keep up.

Charles FitzGerald is the Global Head Of Sync & Brand Partnerships at [PIAS], which looks after Lord Huron in the UK and other territories.

“these platforms are investing a lot of money into the entertainment industry.”

His work life has been heavily impacted by the arrival of Amazon Prime and Netflix in recent times, both of which spend multiple billions of dollars on original content each year.

“There’s obviously a boom because these platforms are investing a lot of money into the entertainment industry,” he says.

“The more shows they make and acquire, the more opportunity we’ve got to get our music into them.”

This explosion of acquired and first-party ‘digital TV’ programming has created a vibrant and demanding market for licensed music, but at a cost.

This explosion of acquired and first-party ‘digital TV’ programming has created a vibrant and demanding market for licensed music, but at a cost.

Per-programme spend by the likes of Netflix on music, say those in sync land, is – on average – around half of that splashed out by traditional US TV broadcasters for similar usages.

“The counter to that is that there’s more programming, so your chances of getting your music are increased – and it means you have to think of new ways of working together to make it worthwhile,” says FitzGerald.

“we also have a duty to make sure that, whatever we agree to do, we maximise the value for our artists.”

One example of innovation being driven by necessity in this digital video world was the recent TV adaptation of Snatch, which premiered on Sony’s Crackle platform.

FitzGerald negotiated a deal for no less than 35 cues within its episodes, as well as the trailer – all provided by [PIAS] artists.

“We appreciate the supervisors in this new world are working with smaller total budgets,” he says. “But we also have a duty to make sure that, whatever we agree to do, we maximise the value for our artists.”

The Netflix and Amazon Prime conundrum – less money being offered per-project, but bigger and more numerous opportunities – is also being felt in another staple of the sync world: advertising.

The Netflix and Amazon Prime conundrum – less money being offered per-project, but bigger and more numerous opportunities – is also being felt in another staple of the sync world: advertising.

“The nature of budgets reducing across the board is definitely there with the agencies, but it’s a huge area of growth overall,” says FitzGerald.

“That’s because there’s not only been an increase in the volume of ads across [broadcast] and online, but also because of the way campaigns are rolled out.

“In the past, a brand might have done a TV ad that ran for a year or even two years featuring one piece of music.

“Now, within just the online component of one campaign, they’ll use multiple pre-roll versions of that advert. And within that, there is a far higher rotation of music often being used in differing contexts.”

“The nature of budgets reducing across the board is definitely there with the agencies, but it’s a huge area of growth overall.”

[PIAS] has certainly seen the benefits of this multi-faceted online approach, which relies heavily on ‘pre-roll’ ads playing on YouTube before a chosen video.

The company is currently busy trying to break Anna Of The North – a Norwegian solo act whose debut album, Lovers, arrived earlier this month.

According to FitzGerald, a YouTube pre-roll ad sync for Google Maps which ran the week of her first single launch was seen (and heard) more than 10m times on Youtube.

Bear in mind that Anna Of The North currently has 1.6m followers on Spotify, and the potential to accelerate an artist’s audience growth through digital video advertising becomes clear.

Another [PIAS] artist, Melanie De Biasio, had her song ‘I Feel You’ synced in the trailer for the latest Alien movie, Alien: Covenant, which was directed by Ridley Scott and released in May this year.

As part of the marketing campaign, the track was also used in a viral YouTube video, which has so far attracted nearly 3m views on the platform.

[video_youtube id=”B4Cmf4BuNgg”]

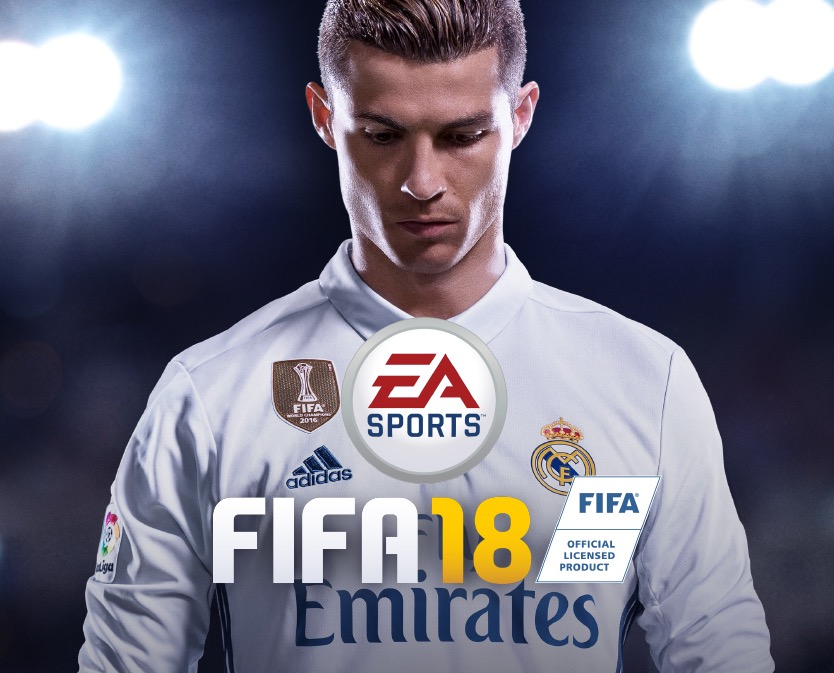

Further examples of how [PIAS] is linking creative sync with artist marketing campaigns can be seen with the recent release of the Fifa 18 soundtrack.

FitzGerald landed three [PIAS] artists in the game (Baloji, Teme Tan and Vessels). The label moved forward the release of Baloji’s single to coincide with the release of the Fifa 18 Spotify playlist and worked in partnership with EA to create artist videos and cross promote their releases to Fifa’s 30 million + social network audience.

Such examples lead us to one of the great conundrums of modern sync: how do you ensure music licensing retains its value when advertisers and TV programme makers can offer better global exposure for artists than most traditional media channels?

Such examples lead us to one of the great conundrums of modern sync: how do you ensure music licensing retains its value when advertisers and TV programme makers can offer better global exposure for artists than most traditional media channels?

“At [PIAS] we have quality artists and music, and so when negotiating on its behalf, you have to get to the point where you can see a clear and fair value exchange,” responds FitzGerald (pictured inset).

“For example, it’s probably true that in the past advertisers had a higher production budgets [for music]. But for a YouTube pre-roll campaign where the production budget is relatively low, the agencies may now focus their budget on the media spend where they can accurately target their key demographics and maximise eyeballs.

“That’s worth something, and we take that into account while trying to find a happy middle ground on the master fee and the terms. Traditionally we may have focused our negotiations on the production budgets, but now media spend is just as relevant.”

“Sync is not, and will never be, pure promotion.”

FitzGerald is unequivocal, however, on the principles by which such a discussion must take place.

“Sync is not, and will never be, pure promotion,” he says. “That’s the one part you can get clashes in this industry; when you get briefs saying, ‘This is going to be great for your artist, but we haven’t really got a budget…’

“The second we start looking as sync as pure promo, the bottom falls out of the market. Worse than that, the value of music overall depreciates.”

FitzGerald admits he’s worried that artist managers in particular are being tempted by the ‘great promotion’ argument – which, he says, “can lead to terrible fees and terms which will only lower general sync fees across the board”.

He is sanguine about the fact that artists are being expected to offer more ‘extras’ to their brand partners than ever before (effectively, reciprocal marketing about a sync using their social channels online).

“Everyone involved wants a campaign to be a success and, to an extent, I understand why brands increasingly expect artists to tap into their own audience to help,” he says.

Talking of value… FitzGerald has little time for online portals which offer unsigned artists the chance to get their music synched in major TV and movie productions, and which then offer this catalogue to supervisors for a sub-market price.

“All they offer is a race to the bottom,” he says. “What’s more, they all seem to want pre-cleared music – meaning your track could end up in an ad for a terrible corporation or political party you fundamentally disagree with.

“At [PIAS], all of our artists have final sign-off on the use of their music. Not giving them that approval is just something we would never do.”

He says this close relationship with artists actually advantages, rather than disadvantages, [PIAS] in the marketplace.

“At [PIAS], all of our artists have final sign-off on the use of their music.”

“On the whole, our artists trust that we understand them and that we have good policies on not doing anything that would make them uncomfortable,” he says.

“Increasingly supervisors want music in a matter of hours: ‘Can we get this by the end of the day?’ isn’t uncommon to hear, although it’s usually impossible!

“Having such a close relationship with our artists helps us meet that challenge: we can ring up a manager or artist and can turn around approvals, edits or demos quickly.”

Happily, although the pressures on sync have never been greater, the opportunity for artists to catch the wave of a licensed TV/movie/advertising ‘moment’ are more bountiful than ever before.

Just ask Lord Huron.

“For a long time, sync seemed to be seen – both internally at record companies and externally – as the ‘cherry on top’ of a campaign, and a nice bit of cash along the way,” says FitzGerald.

“Now no-one would deny it’s a really integral part of almost every campaign.”

He adds: “Traction from a sync can be so significant for an artist, especially internationally. The right sync for the right artist can have a huge impact on breaking them in markets they might not have even really visited before.

“In that respect, sync has become more powerful and more ubiquitous than it’s ever been before.”