What do you see when you look at Daniel Miller?

What do you see when you look at Daniel Miller?

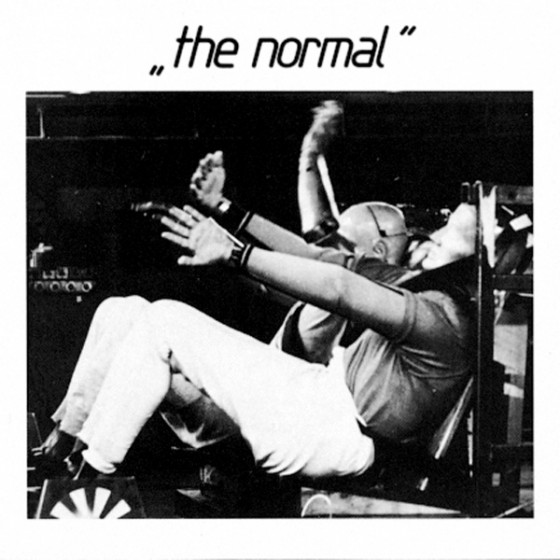

Some of you will recognise a pioneering artist and producer, one whose release of T.V.O.D and Warm Leatherette as The Normal in 1978 forever influenced the appreciation of sophisticated electronic music.

Others might see a record label hero; an exec who’s consistently brought eclectic and thrilling artists to the fore since founding Mute almost 40 years ago – from Depeche Mode to Moby, Erasure, Goldfrapp, Wire, Yazoo, Swans and Cold Specks.

You might also have reasonable cause to paint Daniel as a techno DJ, a canny entrepreneur and a skilled photographer.

Above all of this, though, what [PIAS] founder Kenny Gates sees in Daniel boils down to one important word.

Loyalty.

A huge fan of the Mute label for years, Kenny eventually convinced Daniel to partner with [PIAS]. The two companies are still working together, in more territories around the world than ever before.

But that doesn’t tell the full story.

In 2002, Daniel Miller made the controversial move to sell Mute Records to EMI.

As part of the deal, EMI requested that Daniel move all of Mute’s distribution and licensing relationships over to its mothership.

He refused, keeping a vital chunk of business within the independent music network for years to come – and risking the disdain of the men holding the cheques that were about to rescue his enterprise.

Kenny has never forgotten it.

Neither, we suspect, have Mute’s numerous other independent partners around the world.

Loyalty.

As Kenny discovers in The Independent Echo’s extensive interview below, Daniel Miller can’t help it; it’s an innate value, for better or worse, he’s had since he was a boy.

And thank goodness for that.

Loyal. Likable. Legend.

Daniel, where did you go to school?

I went to King Alfred’s School in North London from 4–18 years old.

At the time it was regarded as a progressive school. This was 1955-1969.

There were a number of unusual things about it for the time: there were no school uniforms, it was mixed, it wasn’t purely academic – they tried to play to your strengths – and it had an arts background, a lot of people in the creative industries went there.

It taught you to be a bit more self-sufficient than a normal school, which just puts you on the path of the curriculum.

How would you describe yourself as a boy?

How would you describe yourself as a boy?

I definitely had a sense of wanting to do things differently. I was lazy. I was really bad at school in an academic sense. I was overweight but I was pretty funny.

We did quite a lot of comedy at school – I’d love to write comedy for a living if I was any good at it. There were a lot of things I really enjoyed but was really bad at like sports, science and playing music.

I was my own person; I am an only child. My parents were refugees from Europe, from Hitler.

“I was besotted with music from an early age.”

They were both based in Vienna, both actors, but they actually met in London. So I had a pretty liberal upbringing, and the school emphasised that. My boundaries were quite broad.

I was besotted with music from an early age. And then when I was about 12, The Beatles and the whole British boom came out; all of a sudden everyone was in a band in school. I was transfixed by it. I was in a band, the worst band, but it was a lot of fun.

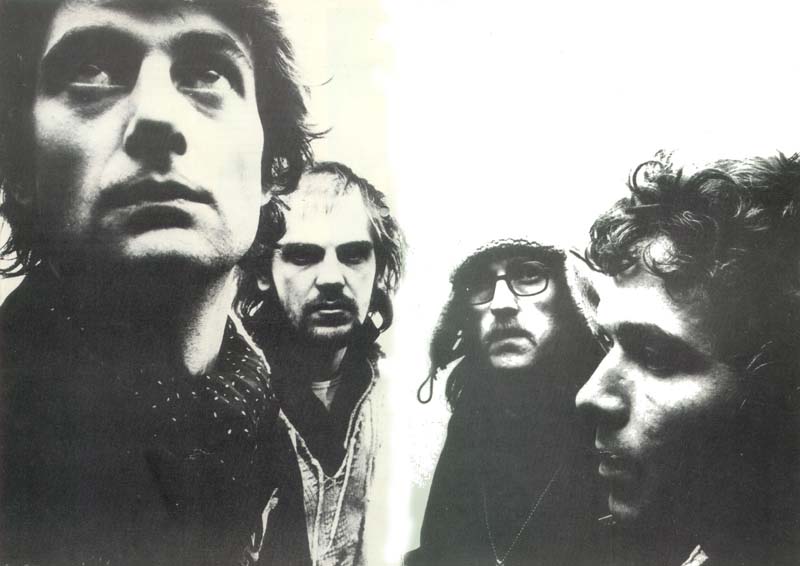

All bad musicians gravitated towards each other. Paul Kossoff was in my class at school – an amazing guitarist who went on to play in Free. He tried to teach me to play guitar; even he failed. Another great musician in my class was Nick Potter, who went on to play in Van Der Graaf Generator (pictured).

Me and three other friends wrote it and performed it around school – it was impersonations of teachers. Taking the piss, basically.

We were really big fans of a show on the radio called I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again. It featured people like John Cleese, Graeme Garden and Graham Chapman. One day we said: ‘Why don’t we send our scripts to John Cleese?’

He wasn’t mega-famous at that time, – We looked him up in the telephone directory and called him. He said: ‘Of course, send me them.’ So we did, and he said: ‘These are really good, come and have a meeting.’

We were 16 or 17 at the time. We went to see him; he was really friendly and gave us some tips and was very supportive. Then there was this new programme, which nobody had heard of at the time, called Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

“Me and three friends wrote and performed comedy at school, impersonations of teachers. Taking the piss, basically.”

They pre-recorded the first five episodes. He invited us to one of the recordings – it was the episode with the famous ‘nudge nudge’ sketch. None of it had been broadcast. We went backstage and met all the guys. It was amazing, really.

After school, my passion was music and my second passion was film. I went to art school in Guildford and did a three-year course in film and TV. It was terrible most of the time. I started there in September 1969. I went for my interview that spring and met all the staff.

During that summer there was a big student uprising in the college. The staff on the course supported the students, and all got fired. So by the time we turned up, it was a completely different staff and curriculum to the one we signed up to. So we went on strike.

Somehow I became a bit of a spokesman – I learnt quite a lot about politics at that time. The college had a little sound studio with three ¼-inch tape recorders in it, and we used to do experiments with tape loops and things like that.

We’d also have guest lecturers; one was Ron Geesin a poet and sound artist who’d just worked with Pink Floyd, and he’d just bought a synthesiser – an EMS SYNTHI A, basically the same thing Brian Eno used in Roxy Music but in a suitcase. That was my first hands-on experience with a synthesiser and it blew my mind. That was around 1970.

Let’s jump to the late seventies: why did you start a label?

Let’s jump to the late seventies: why did you start a label?

Punk was happening, and the whole DIY, release your own records thing was in bloom. Punk rock was great in some senses: it cleared away a lot of shit, but musically I found it quite conservative.

A lot of people quickly moved on to other things. So it was a combination of timing in terms of punk the DIY movement and relatively cheap synthesisers on the market. I felt it was my time – I was driven to make some electronic music.

“There were lots of people record music in their bedrooms in the mid-Seventies.”

I bought a second-hand synthesiser – a Korg 700S. I was working as an assistant film editor at ATV at the time. I came up with a couple of tunes, literally in my bedroom. People think of bedroom recordings as a modern, laptop invention. It wasn’t.

There were loads of people recording in their bedroom in the mid-Seventies. I read about how to put out a single; it was an article by a group called The Desperate Bicycles who pressed their own single and distributed it by bicycle. I knew I’d have to make 500 copies, but I didn’t think I’d sell any.

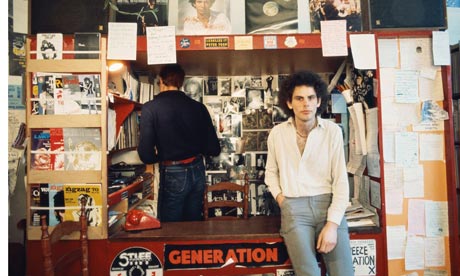

Yes and early ‘78. I got the test pressings and thought I’d see if any shops were interested. The pressing plant was in East London, so the first shop I came to was Small Wonder Records – a famous independent shop and label at the time.

I played the single to Pete from Small and he said: ‘Yeah, not too bad. I’ll take ten.” Then I went to the Rough Trade shop and talked to Judith who was working in the shop. When I asked her if she’d be interested in the record, she said, I’ll go and see Geoff [Travis], who was working in the back.

“Geoff travis played my single in front of all these super-cool people. I was thinking: ‘They Don’t like it…'”

He and Richard Scott, his business partner, listened to it in the shop, in front of all these super-cool people. I was standing there so embarrassed. I was thinking: ‘They don’t like it.’

When it finished they said: ‘We love it, we’d like to do a distribution deal for you. How many are you going to press?’

I said 500 and they said, no, you’ve got to do at least 2,000. They lent me the money to press the extra records. Jane Suck at Sounds Magazine got hold of a test pressing, reviewed it and made it ‘Single Of The Century’. I couldn’t fucking believe it. It then got other good reviews and John Peel played it.

Did you pay yourself royalties?

I ripped myself off! I was not Kobalt: I was not very transparent. The 2,000 sold out very quickly.

Well I’ll drink to that. I think maybe it did 10 – 15,000 in the first few months.

College and alternative radio started playing it in America; I didn’t even know what alternative radio was – I didn’t even know what distribution was!

“I didn’t know what alternative radio was – I didn’t even know what distribution was!”

It was very weird for me as I had no expectations.

It was one of the first post-punk electronic singles; it came at the same time as others like Human League, Cabaret Voltaire, the first Throbbing Gristle single…

I thought I’d bought this cool underground record. It turns out you were selling loads!

[Laughs] I wasn’t selling that many.

If you got in the Top 75 in those days, overnight you’d sell 100,000 records. Woolworths would buy it automatically, along with all the jukeboxes. That didn’t happen.

So selling 15,000 was a successful underground record.

Were you still living with your parents?

My father had passed away, but I was staying at my mother’s place at the time.

How did she feel about it – didn’t she want you to be a doctor or a lawyer?

No, she was totally encouraging. She wanted me to do what I want to do – whatever I had a passion for. She did that with her own life.

By 1960s London standards, my parents were relatively bohemian. They weren’t hippies though!

My father was an actor and had his own German-speaking theatre for refugees during the war. He was an indie! I got a bit of both of them.

I was helping out at Rough Trade doing a bit of promotion work.

I was in a position where I had to make a decision: I was getting demo tapes, which I didn’t really like that much and I didn’t want to start a label.

“I shared a similar vision with Frank, who was fad gadget.”

Then I was introduced to Fad Gadget [Frank Tovey] by a guy called Edwin Pouncey – the NME punk cartoonist who went under the name of Savage Pencil.

It was the first thing I’d heard that I’d really liked. Then I met Frank, who was Fad Gadget, and we got on really well.

We shared a similar vision and I said: ‘Let’s make a single.’ That really was the beginning of Mute Records as a label, as opposed to just my own thing.

Why call it Mute?

I had a list of 100 names and it was on there.

The idea of Mute came from film. When you shoot film, you normally shoot it with sound. When you shoot it without sound, it’s called ‘mute’.

Because I was working in a cutting room, an editing room, I saw this word Mute everywhere. I liked it.

How did you meet Depeche Mode?

How did you meet Depeche Mode?

Fad Gadget’s single came out in 1979 and we started working with a couple of other artists – D.A.F, significantly, which was the first album release on Mute.

Fad Gadget made our second album, and he was promoting it doing gigs around London. He was booked to play The Bridge House in Canning Town.

The guy who booked it, Terry Murphy, was a real East End guy, who liked to support East End musicians; he knew Frank’s father, who was a big East End figure working in Smithfield’s market.

Terry booked Depeche Mode to support because they were from Basildon, Essex, which was an East End overspill town. I saw them during the soundcheck and they looked really dodgy, in homemade New Romantic clothes. They also looked really young.

“I saw depeche mode during the soundcheck and they looked really dodgy, in homemade new romantic clothes.”

They had three little synths supported on beer crates, and the lead singer had a light that he shone upwards to make himself look gothic. But when they came on stage that night, I watched the first song and just thought: ‘What?! That’s fucking incredible! What the hell’s that? I’m sure it will go downhill from here.’

But it didn’t – it just got better and better.

Most of the songs they played in their 30-minute set ended up on the first album. I couldn’t believe what I’d heard; great songs, unbelievably well-arranged. I went backstage and said: ‘Hi, I’m Daniel from Mute. I really enjoyed it.’

They were being all cool, but said: ‘We’re playing here again next week supporting someone else.’ So I told them I’d come down. I took a couple of people with me including NON – Boyd Rice – who was a big pop fan, and my first employee, Hildi Svengard.

They both said: ‘Daniel, you’ve got to do this.’ I went back and said to the band: ‘Do you fancy doing a single?’ They said yes, and it was Dreaming Of Me.

You were early to sign them…

I remember, typical of the British press, that there was an article [on the next wave of supposed New Romantics]. Depeche did a gig at The Hope & Anchor in Islington: Roger Ames came down, so did Chris Briggs – all these major label A&Rs were there, all trying to sign the band.

At the end of the gig, I went back stage and all these people were already in the dressing room saying: ‘Mute’s a nice little label, but they’ll never get you any success. There’s only two people working for it.’

“The majors were so arrogant and condescending. I thought: ‘Fuck you.'”

The band just said: ‘Yeah, but we’re going to stick with them for the moment, see how it goes.’

They put their trust in me and I wanted to return that trust by doing the best that we could do. I was determined to make it a success… I was convinced we could do it on our own. The majors were so arrogant and condescending, I thought: ‘Fuck you.’

The band were offered quite big advances [which they turned down to stay with Mute]. We didn’t have a contract, no lawyers, no managers: we sold a fuck of a lot of records and they made a good amount of money without any of them.

[video_youtube id=”ZFnEhwmpjXI”]

Do you remember the first time it crossed your mind that what you were doing was meaningful – that it was changing culture and people’s lives?

You have to remember that in the early ‘70s electronic music was still elitist – people couldn’t engage with making the music because everything cost a fortune.

I was a huge electronic music fan though, and in my head electronic music was the ultimate punk music especially as much cheaper synths came on the market – you didn’t even need to learn three chords.

So right from the beginning I wanted to communicate that electronic music could be homemade, anti-elitist – that was the message I was sending out when I released that first single and I’d like to think that I went some way to achieving that.

What’s the biggest-selling Mute album of all time?

What’s the biggest-selling Mute album of all time?

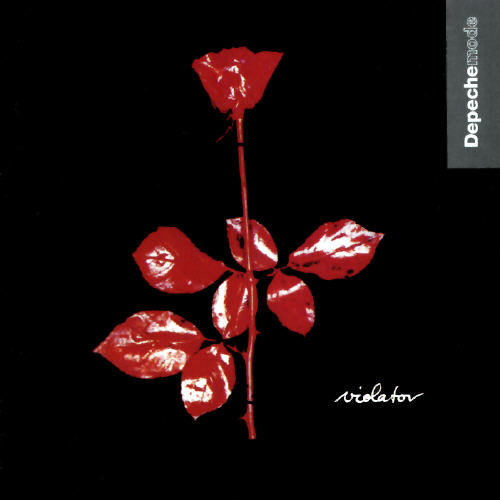

It must be Violator. That sold around 10m or 11m.

[Moby’s] Play worldwide was the same, but we didn’t have the rights for north America.

Have you ever dropped an artist? If so, why?

Of course, yes. Loads! The idea we didn’t drop artists was a myth that was around Mute in the ‘80s or ‘90s.

If I feel that I’m more excited by an artist than they are about themselves, that’s a reason to drop an artist.

“we went through a phase of dropping a lot of artists who’d run out of steam.”

There was a phase where we dropped a lot of artists, and it was because they’d run out of steam; it wasn’t to do with money – it was creative reasons.

They tended to be relieved, actually – they felt obligated to make records but weren’t enjoying or making very good music.

I’ve heard you say there are no priority artists at Mute. Can you explain?

Yes. With every record, whether you think it’s going to sell a thousand or a million, you should do the very best possible job to ensure that it attains those targets.

Of course an artist that’s going to sell a lot of records takes up a lot of time.

But I hate the word ‘priority’. Why would you release a record and not work it to its full potential? That doesn’t make any sense to me.

What makes Mute different from other labels?

I think Mute has to be different from other labels.

Let’s put the majors to one side because there’s such a clear difference between us and them: especially now, the majors are very focused on pop. That’s not a criticism, that’s a fact. Everything’s very track-driven these days.

I love pop, but not in the conventional sense. Majors are very numbers-driven, sometimes only numbers-driven. I’m not criticising the people who work there, but the natural corporate structure is all about numbers.

“Who can honestly tell the difference between universal, sony and warner?”

Mute is about working with really great artists, particular artists. I think we have our own character because of the artists we choose to work with and the way we work with them.

I’m a fan of Warp, Domino and many others, and they’re all different. Independent labels like that still have their own character – they’re not homogenised.

Who can honestly tell the difference between Universal, Sony and Warner?

Not many other labels have our breadth of roster. Our understanding of artists as a team is very good. We’re not fashion-driven. And we’re really, really nice people. I think we’re even nicer than [PIAS].

You might be right. You still seem to really enjoy what you do. You recently turned to me in a moment of passion about Mute and said: ‘I love it!’ It seemed sincere.

I have a personal rule: so long as I like more than 50% of what I’m doing, I’m really, really happy.

The reality is there’s a lot of shit you have to deal with on a daily basis.

But if I think things are moving forward with the company and our artists, I feel very lucky.

You’re a leader, a boss of a label. Have you felt the loneliness we all feel in that position? How do you deal with it?

Sometimes, yes. Of course. There were moments in the history of Mute, especially when we sold to EMI. I remember the day I signed about 500 fucking contracts…

You feel very responsible: you can blame everyone else or criticise everyone else, but in the end, you’re responsible, and you have to deal with it on a personal level.

A good example is Vince Clark. He was in Depeche Mode and had huge success very quickly. Then he was in Yazoo and had instant success. Then he did Erasure [first record], and it was a flop.

“So long a I like more than 50% of what I’m doing, I’m really, really happy.”

From the age of 18 to 24 or something, he couldn’t put a foot wrong. And for whatever reason, Erasure started really badly.

We questioned it together, even getting to the point of saying, ‘Maybe you should go to another label.’ I felt an incredible weight of responsibility – firstly because it was a great record, but also because Vince had been incredible loyal to me.

I hate it when a record doesn’t do as well as it should do.

Even though we still had Depeche and Erasure, we had some years in the mid-to-late Nineties which were very poor, very light.

Depeche were making records less frequently, Erasure’s sales had started to go down. It was the Britpop era, which I had no interest in at all. Britpop represented everything I hated – the antithesis to why I started Mute; it was very retrograde, non-progressive yet all-pervasive, especially in the mainstream media.

Inevitably, we had a few financial issues. We’d always worked with individual distributors around the world – [PIAS] in Benelux, Virgin in France etc. – and I still think that’s the best way of doing things. It allows you to pick the best people in each country.

But I needed some cash. I thought maybe if I did a worldwide distribution deal I could get more money. Mute was not very highly regarded in those days – a lot of people felt it was over. I had staff, artists, and I was being offered not-very-good deals.

“Britpop was everything I hated; it was very retrograde, non-progressive but all-pervasive.”

And then, like the cavalry coming over the hill, we had [Moby’s] Play. A lot of people believed in Play – including you, Kenny – before it was a hit. I totally believed, obviously. Yet we had released three singles and nothing was really going on.

Then we released a fourth single, having asked what I should have asked myself on day one: ‘What’s my favourite track?’ Not ‘what is the obvious single?’ It was Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad.

It exploded. All of a sudden, I was regarded as a ‘genius’ again. I was ‘past it’ for a long time before that, of course, but that’s the music business for you.

Emmanuel De Buretel, who I’d known since the beginning of Mute and who was running EMI Continental Europe, had always wanted to buy Mute. I thought: ‘Okay, we just sold 8m records, we’re in a really strong position. Do I really want to go through all of that shit again?’

So I gave Emmanuel a list of what I wanted; it was less about money, although that was on there, and more about creative control. He said yes to all of them. Plus he was starting an alternative distribution system and wanted to make it global with Mute as the lead label.

Just before we were about to sign the deal, Emmanuel’s boss Ken Berry – who’d I’d known for years – was fired. Literally as I was about to put pen to paper, Emmanuel got a new boss, Alain Levy, who came from a very different world.

“I gave EMI a list of what I wanted. It was less about money, more about creative control.”

He signed off on the Mute deal though, no problem, but things had changed.

We were still based on Harrow Road in that crazy building. And it was all fine. But Ken Berry had been a bit of a mentor to Emmanuel. After he went, there was tension between Emmanuel and Levy. Eventually, it got too much and they parted company – Emmanuel left EMI.

Levy was still treating me very properly at that point. He let me decide who I reported to.

I definitely didn’t want to be reporting into the UK, so I said I’d stay with Continental Europe – where JF [Jean Francois Cecillon] took over from Emmanuel.

Let’s say we came from two different worlds: he’s an Arsenal fan, I’m a Chelsea fan… Then EMI had their own problems, and we got caught up in it.

Do you regret it?

No. I can’t possibly regret it. It was the right thing to do at the time, it gave Mute stability and for quite a few years we had real autonomy.

It was an interesting experience, but in the end it became impossible. Creatively, EMI never questioned what I signed – they kept their word. The problem was international – which was always very important to me.

“breaking artists internationally became impossible at EMI, unless it had been a hit in the UK.”

I felt that you couldn’t just break artists in the UK, you have to do it over a number of territories for them to have longevity.

That became impossible at EMI. They wouldn’t release anything internationally unless it had become a hit in the UK. It wasn’t that they wouldn’t let me sign anything, it was that I didn’t want to sign anything. The kind of artists I wanted to sign wouldn’t survive in that system. So I decided to leave and start again.

Are you aware that what you’ve achieved with Mute is extraordinary?

Thank you, but I don’t think of it that way. I live in the moment. I don’t think about the past too much: that only really happens when I’m at a gig and someone comes up to me and says, ‘I grew up with your music.’

Obviously, that means a lot to me. I’m proud of it.

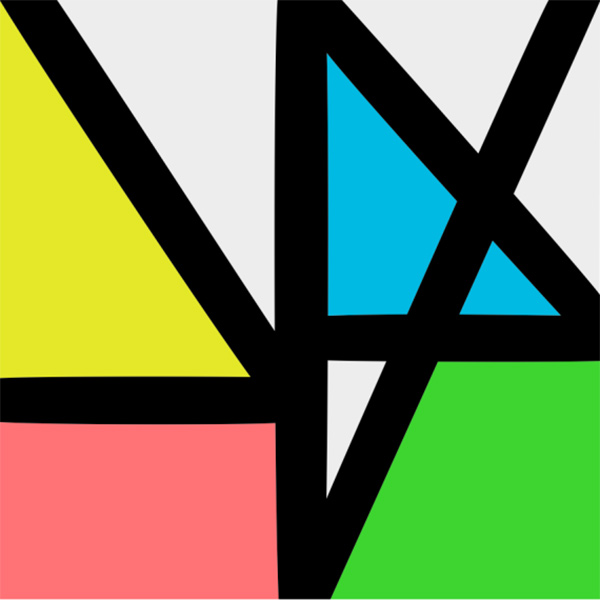

But right now, I’m concentrating on the pre-orders on the New Order record and what the extended 12” sounds like.

Tell me about New Order, then. Their new album, Music Complete (pictured), comes out on Mute this week. How did you come to sign them?

Tell me about New Order, then. Their new album, Music Complete (pictured), comes out on Mute this week. How did you come to sign them?

Obviously, I’m familiar with their music. I’d met the band a few times over the years. And I knew Tony Wilson well. Anyway, they decided that they didn’t want to stay with Warner Bros.

Nicki [Kefalas] from Out Promotions – who does both their TV and radio and our TV and radio promo – suggested they come and see me.

I talked to Rebecca Boulton and Andy Robinson who manage them. I went up to meet the band, we had a lunch and had a very positive discussion about their vision for the project and we got on well.

“I heard some work-in-progress things [from the new order album] that I thought sounded very special.”

I was nervous, obviously, as I had no idea what the music would be like – and, of course, that was the most important factor for me.

They played me some rough work-in-progress things that I thought sounded very special.

The band and their management did a lot of due diligence on Mute – the management met our German and American companies and spent a lot of time with us – we all felt comfortable. So we said: ‘Let’s do it.’

Are there values at Mute as a company?

In a very broad sense. They are so built into our DNA we don’t even think of them. It’s not like [affects American accent]: ‘The core values of our operation are creatively, transparency, sustainability and diversity.” I’ve never had to think like that, thank God.

Have you ever felt betrayed professionally?

Once or twice. Betrayal gives me inspiration, though.

‘Betrayed’ is a really big word, so I’ll say ‘let down’ – this is the first time I felt really let down: When D.A.F came to Mute, they slept on my floor, I took care of them, basically we were all broke.

Their album was the first on Mute so it had a very special meaning to me and I did everything I could for them. And then they left to go to Virgin.

“I realised I never wanted an artist to [leave for another label] again.”

Of course I was really pissed off. I remember it really clearly: I always got on best with Robert Gorl, the drummer. I was sitting in my car with him at the time they decided to leave and he played me some tracks from the forthcoming album – the one that wasn’t going to be on Mute.

I thought, ‘Fuck, that’s so great.’ And I played him some Depeche stuff – we had just started working with them – and he went, ‘Fuck, that’s so great.’

It was a weird moment but it was inspiring too. I realised I didn’t want it to happen again.

Are there any people in the business who stand out as real mentors or inspirations to you?

Are there any people in the business who stand out as real mentors or inspirations to you?

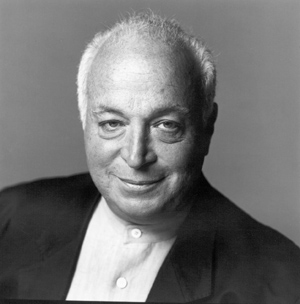

Seymour Stein (pictured), who I got to know really early on. He licensed TVOD, and was the first American music person I met. His energy and spirit were amazing, and obviously I loved the bands he signed.

I still feel close to him today. We hang out and get on. There’s been different people along the way – Rod Buckle from Sonet at the beginning, certainly.

Without Rough Trade’s enthusiasm and confidence at the beginning, things could have been very different. But once Mute got going and Rough Trade had huge success, we were all caught up in our own chaotic work and didn’t really have such a close relationship with Geoff.

I never thought of the other independents – Factory, 4AD, Rough Trade, Cherry Red – as competitors. I felt we were collaborators working together to build something special. That’s still the case, really.

What are your ambitions for the next decade?

Stay alive and keep doing what I’m doing now. Keep being innovative and work with great artists, whether they sell a thousand records or a million records.

Here’s the question I ask everyone: Are you a romantic?

In what sense? I’m reasonably good at buying flowers for my girlfriend if that’s what you mean! I wouldn’t describe myself as a romantic – a dreamer, maybe. It depends on your perspective.

Before you did the EMI deal, you did deals with your individual licensees – including [PIAS] and others around the world. It cost you serious money but it looked after us. Are you aware that demonstrated supernatural loyalty?

Before you did the EMI deal, you did deals with your individual licensees – including [PIAS] and others around the world. It cost you serious money but it looked after us. Are you aware that demonstrated supernatural loyalty?

No it didn’t, not really. We’re working in a very human business.

Music is emotional. I can’t separate the human from the business side.

If I like people we work with who do a good job for me and my artists, I can’t, you know…

Well I’m afraid that’s what I call a romantic, Daniel…

Okay. So long as you don’t call me a new romantic, we’ll be just fine.

Do you remember when [PIAS] first approached you to be your licensee? What did you think of us?

Well I don’t remember a specific time; I just remember a constant barrage of requests. I thought you were arms dealers, with a cover of the music industry. No, I’m joking. I remember a period of time when you hassled me a lot but we were already licensed elsewhere…

That bloody loyalty again!

Yes, you had to break it – but I’m very happy you did.

[Pictured: Daniel Miller. Credit: Joe Dilworth]