You can’t write the history of the British independent music industry without writing the history of Ace Records.

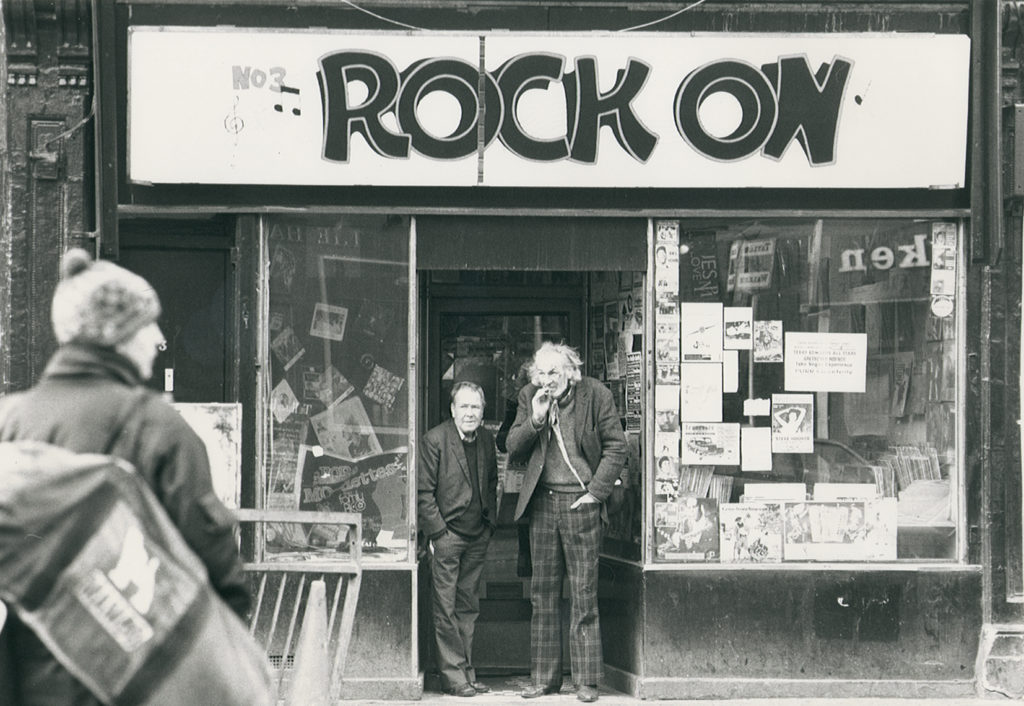

The foundations of the legendary label began back in 1971, with the birth of Rock On – a vinyl-peddling stall in a flea market off Portobello Road.

By 1974, Ted Carroll had expanded to Soho, where he hired former Queens University Social Secretary Roger Armstrong to deal with the customers.

It didn’t take long before Carroll – who had just managed Thin Lizzy through their Whiskey In The Jar heyday – spotted an opportunity to fulfil a long-held ambition.

“I wanted to start a label to reissue rock’n’roll, mainly,” he tells The Independent Echo of his then-aspirations. “I knew from dealing with majors that they weren’t so interested in back catalogue at the time, so we started licensing records from them and put them out.”

Ace Records began life in 1975 as Chiswick Records – to which Carroll and Armstrong signed their first band, The Count Bishops.

Another early signing, Sniff ‘n’ the Tears, had a bone fide international hit in 1979 with Driver’s Seat, although EMI’s internal politics over their sales force meant it never became the smash it could have been at home.

In 1978, it officially became Ace when Chiswick signed a licensing deal with EMI, but the British major didn’t want to take on any back catalogue from the indie – meaning that Carroll, Armstrong and their partner Trevor Churchill had to find a new brand for their historic discoveries.

After a quick chat with the founder of the original Ace Records in Mississippi – Johnny Vincent – the legendary British company was born.

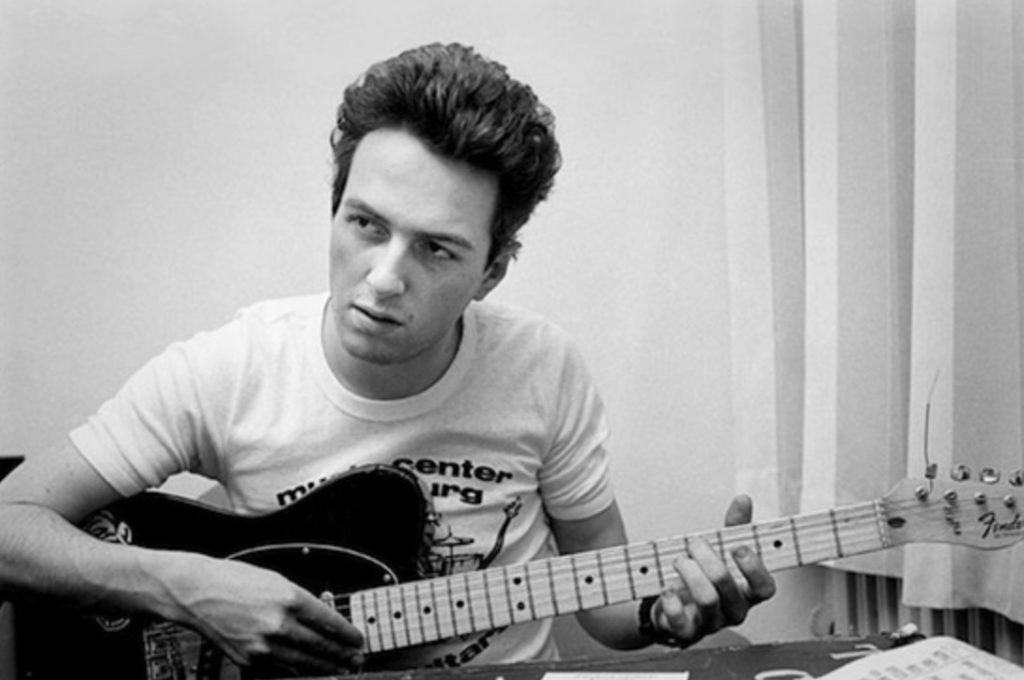

In Chiswick’s early days the label showed itself to be on the frontline of culture, releasing early cuts from the likes of Motörhead, Joe Strummer (in the 101’ers), Billy Bragg (in Riff Raff), Jim Kerr (Johnny & The Self-Abusers) and Kirsty MacColl (in Drug Addix).

But over the past four decades, Ace Records has become primarily known for its lovingly-presented reissues and compilations of spine-tingling music from the worlds of soul, jazz, country, rockabilly, blues and more.

Here, [PIAS]’s Kenny Gates sits down with Carroll and Armstrong (pictured with fellow business partner Trevor Churchill) to ask how Ace came to be – and what drives the two entrepreneurs to keep doing what they do…

Are you the longest partnership in the British independent music industry?

Roger: I think we’re the longest-running record label still in the same hands – certainly in the [UK].

Ted: And we own it completely. We never sold out to anybody. We did one or two licensing deals with EMI and people along the way, but it’s always been controlled by us. A year after opening the Rock On market stall, I really wanted a shop so I opened one in Camden Town. Eventually, the stalls went by the wayside as the record label was building up – Rock On in Camden was my main shop until 1996.

Roger: We started in Chiswick [Records] in August 1975. We had a couple of false starts: then we found a band called Chrome playing on the Holloway Road, in the Lord Nelson pub, and they were a good, tough R&B band. But By the time we got to make the record, we cut some sides with them as Chrome, a guy called Mike Spenser joined them as lead singer from New York – he came into the market stall and was looking for bands that sounded like the Stones. He ultimately ended up inveigling his way into what had by then become The Count Bishops, who were our first release.

I took them into Pathway Studios and which became legendary for The Damned, Elvis Costello etc. I remember we took the band in one steaming hot August night. The drummer virtually had his head on the snare it was so hot, and Ted turned up with a big box full of beers. Everybody had a bit of a drink and off we went to record more tracks. We cut about a dozen tracks that one night.

Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity is apparently based on Rock On. Do you see yourselves in it – telling off the customers when they didn’t know about artists?

Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity is apparently based on Rock On. Do you see yourselves in it – telling off the customers when they didn’t know about artists?

Ted: No, we tried to avoid that. But we certainly didn’t stock any shit – when we were buying in collections, we’d only take the records we thought were worth having. The rest we’d leave. So you didn’t have to dig through piles of shit to find the good stuff at Rock On.

Roger: It’s the old adage: ‘What kind of records do we sell? Good ones.’ It’s as simple as that.

Was it also a social centre?

Roger: It was amazing. I would go over there late morning on a Saturday with no plans, and you’d end up somewhere in the early hours of the next morning.

Ted: It drew interesting people. Our regular customers included virtually all the punk bands, Jimmy Page, Bob Dylan came in one day, Lenny K – all sorts. It was a real meeting place.

What did Bob Dylan buy?

Ted: He bought loads of mainly white US Gospel records.

Roger: He was rehearsing at the Electric Ballroom next door.

And Joe Strummer came in as well?

And Joe Strummer came in as well?

Ted: Strummer was an early customer; he used to come in every Friday looking for obscure New Orleans blues records

Roger: The connection there is the second record we put out after the Count Bishops was Brand New Cadillac by Vince Taylor. Trevor [Churchill, Ace’s third partner] was in with us by then – that was the only reason we got the licence from EMI, because Trevor had worked for them.

That was your first reissue?

Roger: Yes. The idea Ted had for the label was to record new bands playing old-style music, but then we would reissue old records as well. Our third record was Keys To Your Heart – the 101’ers with Joe Strummer. The Clash went on to record Brand New Cadillac a couple of years later, which was a nice touch.

Ted: There was a lot of cross-pollination between the old and the new; people like Joe Strummer wouldn’t have known Brand New Cadillac until he heard the reissue.

Chiswick was your original frontline label: it released the 101ers, Johnny and the Self Abusers and Motörhead’s first album. Do you still have that debut Motörhead LP in your collection?

Roger: Oh yes. Ted just did the 40th anniversary edition – one of the biggest sellers we had this year.

What were the terms of your licensing deal with EMI?

What were the terms of your licensing deal with EMI?

Roger: It lasted from 1978 to ’81.

Ted: They had the distribution and promotion [power], and we were pulling the devil by the tail financially. We licensed Chiswick to them – which was new recordings – and then we had [catalogue] rock’n’roll, which they didn’t want. We decided we’d move all of that stuff into another label.

Trevor suggested the name Ace, because we’d licensed stuff from Ace Records in Mississippi, so I called up Johnny Vincent and said: ‘We’d like to start a label called Ace.’ And he said no problem. We put Ace through an independent distributor, Pinnacle Records, and then we started [sub-labels] Big Beat for ’60s stuff, and then Kent for Soul.

Do you have any mentors who inspired you to do what you do?

Ted: Not really. The London American label was fantastic in the ’50s in England – all the American independents like Sun, Atlantic all came out through London. And then in the ’60s, Sue records led by Guy Stevens – those were inspiring. But from having a record shop, you learn what people want and what’s good. I’d been a rock’n’roll fan since I was a kid; I went to see Bill Haley in 1957 the first time he came over to the UK.

Roger: We were inspired by the guys who were independent, the Chess brothers and others. When we started, we were a real grass roots independent – when we put the Count Bishops out, Ted would distribute the records from the back of his car.

Ace is a label which kind of becomes the legacy of other labels. You’ve re-released from everyone like Fame to Fantasy, Flying Dutchman… Do you know how many albums you’ve put out?

Roger: If you count everything – 45s, LPs, CDs, boxsets – as one piece each, it’s just short of 5,100 items. Defining ACE in terms of our USP, we’re the compilation kings.

You are real music fans: you’ll do a deal with a label, but then you go into the vaults and spend a long time digging around. Do you have a physical/sexual/mental pleasure in the vaults, like a kid in a toy store?

You are real music fans: you’ll do a deal with a label, but then you go into the vaults and spend a long time digging around. Do you have a physical/sexual/mental pleasure in the vaults, like a kid in a toy store?

Roger: It’s the heart and soul of it.

Ted: I’ll give you an example: on my first trip to America, I did a deal with a company called Starday Records and a guy called Pappy Daily, who produced George Jones and was a big record distributor. I came back [to Starday] about a month later with Ray Topping, the blues detective – he knew more about old artists than anyone else – who had recommended doing this deal with Pappy.

In those days we were copying onto reel-to-reel analogue tapes to bring home. We came across this couple of tracks at the end of a George Jones album session by a guy called Hal Harris, who was a session guitarist who did a lot in Houston. We found two fabulous tracks, two songs of [Harris] – Jitterbop Baby was one – and they were totally un-issued. We asked if we could put them out, and Pappy called up Hal Harris, who was a preacher by this point. He said he didn’t mind. We put them on a album, but also released them as a single, in 1978. They’re still in catalogue – they’re not PD – but they’ve been bootlegged so many times. They’re fantastic.

Roger: I had this Otis Redding thing, when I was searching through the Stax [archive] for Fantasy. It was about two in the morning and I just thought, ‘Come on, one last reel.’ I opened this four-track tape and a piece of paper fell to the ground with Steve Cropper’s handwriting on it, which I recognised by then. It said: ‘Dock Of The Bay.’ I put the tape up and heard Ron Capone – the engineer – say, “Dock Of the Bay, Take 1.” Chills went down my spine. Nobody had played that tape [since it was recorded].

There was the familiar guitar intro, but then on Otis’s vocal track, he starts impersonating the seagulls; he was dead by the time they finished the record and that must be where they got the idea to put the sea and seagull noises on it.

You’re more than compilation kings, then: you almost give a rebirth to amazing music.

Ted: It’s about the desire to disseminate the knowledge, to turn people on to interesting records. The shop was an extension of that, and then the record label is the ultimate extension of it. Now music’s online, we’re getting to corners of the globe you could never have reached with physical product.

Roger: CD was perfect for us though – you could do so much with images and notes with that format, and you could put 28 tracks on there, so you can really tell a story. We’re very theme-orientated – we do songwriters series, the producers series – and we’ve kind of turned the compilation into an art form.

What gives you the fire to share those things people don’t yet know?

Ted: Amazingly, after all this time we still get a kick of out it. When we did the Brand New Cadillac 45 we learned a lesson – we got the tape from EMI, we went into the cutting room and we wanted a nice loud cut. The engineer, Ray Staff, put the tape on, played it back through those great speakers and we were kind of underwhelmed. We suddenly realised that the guy who’d cut the original 45 had done things; there was a guitar intro and he’d brought the volume up, he’d put a tiny bit of reverb on it. Ray played around and was eventually able to emulate the cut. We were very happy and everyone loved it because it sounded as good as if not better.

Roger: If you wind forward a bit, the other side of Ace which is different from any other company is that we built our own studios. We’ve got two state of the art, balanced rooms with amazing equipment and two engineers that have been at it for years. That’s all on the premises; if ever one of the engineers wants to know whether something’s right or wrong, he comes up here or we go down there and we work it out. The rooms cost a couple of hundred grand each to put together; the whole thing is proper Abbey Road-level. From very early on, we were very concerned about quality.

Ted: 20 years ago, we could have something on the schedule that would sit there for a year because we were looking for the perfect tape source for a particular track. It’s got to the stage now where people know that Ace Records equals sound quality.

How have you stayed in business for so long?

Ted: I just read this book Going For A Song – it’s a joy.

One of Geoff Travis’s proudest memories is that at Rough Trade, he didn’t take any more money than everyone else was earning. But with Ace and Chiswick, we often didn’t earn as much as the staff were earning! I remember Trevor in 1977 or 1978, got a call from the bank one afternoon and they said: ‘We’ve got three cheques here and it’s going to take you X amount over your agreed limit so we can’t pay them all.’ Trevor had to bounce his own salary cheque! That’s the way it was.

Roger: Part of the reason we’ve been able to stay around is that Trevor is very meticulous about accounting. It would disturb him really badly if he couldn’t pay someone. So that end was always impeccable – everyone got what they were due. The royalty statements were easy to understand – we had clarity going for us. So a lot of artists stayed with us.

Ted: The record industry has got such a terrible reputation [for paying artists] and it’s true to a certain extent, but we’ve always prided ourselves on that. We’ve kept the overheads down and kept our hands out of the till.

Were there any times you didn’t know if you could keep the lights on?

Ted: A few times, in the early days. When the CD came along we found that, suddenly, we were making quite good money. Before that we were always pulling the devil by the tail financially.

We were very careful. For instance, we put out the first Motörhead album and nine months later Doug Smith came to us and said, we’ve been round one or two majors and they weren’t sure about the band’s heavy duty, Hell’s Angels-like image. Doug said, ‘Do you want to do another album? We need about £15,000 for recording costs and other things.’ Myself, Roger and Trevor sat down together to work it out.

We knew we’d sold a lot of copies of the first album, so we knew it would be good to have another album from Motörhead, but we also knew it wouldn’t just be £15,000 – they would get through that fast! We really wanted to do another album with them, but we made the conscious decision that we couldn’t afford to do it, so we passed.

Roger: We started working with Fantasy, who had been distributed by RCA, and they bought Contemporary Records, a west coast jazz label. I knew Bill Belmont who was their overseas guy; he came to me and said, do you want to take on Contemporary because our RCA deal is running out and I don’t want to give it to them? I said, Yeah, great. And then he said, the RCA/Stax deal is [going to expire soon] – do you want Stax too? So we took Stax. Then he comes back and says, the RCA deal is completely running out do you want the lot – Creedence, Prestige, Milestone, Fantasy. This was huge!

We sat down and talked about it, and said we’ve got to seriously think if we have the resources; there were heavy advances involved and it was a tough deal. We knew that if we didn’t do it, our rivals would and we’d be stuck. And then shortly after that, Giles Peterson came to us and the acid jazz thing started to happen. I remember when the dust settled on the Fantasy deal, we looked to see what we’d done on [jazz-funk/soul-jazz imprint] BGP, which was nearly all Fantasy, and we’d sold just shy of two one million records – on an idea that came up in my office one afternoon!

You told me an anecdote about Lemmy over lunch. Can you repeat it here?

You told me an anecdote about Lemmy over lunch. Can you repeat it here?

Roger: Oh yes. When [Motörhead] went to Bronze [for their second album], Lemmy said to me: ‘I’m really sorry to be leaving you and Ted.’ He was being apologetic. I said, it’s fine Lemmy, they’ll do well for you and have more money than we do. And as he walked away he said, ‘Anyway, you got the best record we’ll ever make.’ Which is not true, but it was very nice to hear! He was a really nice guy.

Have you got a proudest moment in your career?

Roger: I produced The Damned’s Machine Gun Etiquette, and I’m still proud of that record. It helped turn them round from being a band who were on the way down to being a hit act.

Ted: When Sniff N The Tears went Top 20 in America, we felt pretty cool about that. But we’ve missed stuff as well, The Undertones and other stuff.

Roger: On the catalogue side, the Golden Age series stands out as a real benchmark. And one thing in recent years I’m very proud of is that we did the official music from Bob Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour – three double albums. The work that went into that was incredible. And then on a whim I decided to get lots of different people to write sleeve notes, which runs the gamut from Elvis Costello to Pat Boone.

Do you feel you’ve contributed meaningfully to the history of the music business?

Ted: Definitely, because we’ve made so much great music available for people who want it.

Roger: The fear when you’re doing oldies and reissues is always that your audience is going to die on you! But the truth is, especially in this country, genres like Northern Soul are always bringing young people in.

Do you feel comfortable with the whole streaming explosion?

Do you feel comfortable with the whole streaming explosion?

Roger: What it lacks, in terms of what we do, is information. We half-jokingly have been known to say we sell information and photographs and throw in some music for free! The notes are entertaining, too. The thing about streaming and download is that you can’t connect the [historical] information to the music and that for me is why I don’t regard it as good a way as delivering music [as physical].

With a vinyl LP, you only have so much room for your notes on the back, but it’s a beautiful thing; with the CD, you can pack it full of notes with a large track list. I’m not knocking streaming – it’s a fantastic income stream. It’s made a lot of our music available to a younger age group who might not have gone and bought a CD at a higher price, but now they find it through Spotify and others.

Ted: We’re also reaching all over the world – from Egypt to Israel, South America and more. That’s incredible. I look at the statements and think, Why has someone in Estonia downloaded this track 27 times? That’s a great development.

Roger: What works on streaming playlists for us is when you get a good hook; I’ve done one called ‘What’s That Racket?’ which is garage rock from the 60s, punk from the 70s and British garage bands from the 80s. It’s all the stuff that makes a noise! So we’re using our repertoire with playlisting to try and attract people to the catalogue. The other thing is that through playlists we’re trying to find a way to brand Ace; the one thing over the years that’s always been a real strong point for us is the name.

Some people say that labels and artists risk losing a little bit of identity on streaming…

Roger: A big selling point of ours is that it’s on Ace; people looking through the racks and thinking, this is on Ace, I’ll buy it.

We are the tipping point – they know it will sound great, be of good quality and have interesting notes. That’s the one thing lacking online – how do we push the brand we’ve worked on for 40 years?

Are you romantics?

Ted: In that we truly love the music, yes – Trevor and Roger the same. It’s great that we’ve been able to make some money out of it, but it’s much more important that we’ve made it available to people who wouldn’t have heard it otherwise.

Roger: When I was growing up as a kid I was buying Stax singles, and now I’ve sat out drinking wine till far too late in the morning with Steve Cropper. If you told me as a kid I’d be hanging out in bars with the guitar player, I’d have gone, No way! There’s a great romance in that idea.

Ted: We’ve always done these ‘service to humanity’ records, which might not sell, but what the hell – it’s important it gets out there. You get a below-the-wire kickback from it because people dig it and it adds credibility to your label.

Roger: I went through the Stax vault to do a Mabel John’s CD, which was Little Willie John’s sister. She loved it because she’d recorded for Motown and for Stax but had never released an album. She’s in her eighties. She came over to London for something and we all had dinner, and she regaled us with stories. You can’t buy that stuff – you work for it. Lots of people we’ve worked with have never left America or even left their State, and if we can help them have a career again where they suddenly get to tour Europe. It’s another world, and it’s precious.

What was it like meeting Joe Strummer?

What was it like meeting Joe Strummer?

Roger: Joe was a funny one.

Ted: A nice guy.

Roger: The last time I met him, it was at a world music event in hackney. I’d gone upstairs in this bar area and was looking for somebody, and there was Joe. I’d been ill and had grown this beard. Joe walks towards me and I said: ‘It’s Roger, Joe, remember? Chiswick Records?’ And he turned to me and said: ‘Is Ted dead yet?!” It was because Ted was lacking in hair and had the beard [back in the day] they thought he was so much older than everyone else! Joe was like that.

When the 101’ers broke up, I was standing in the [pub] getting a drink for somebody and Joe taps me on the shoulder – we hadn’t even put the record out. He said I’ve left the band and started a new band with this guy – a skinny kid was standing behind him, who was Mick Jones. And I said, Well thanks a lot! But the way he told me was to ask, Have I done the right thing? That says a lot.

Joe had this convoluted way of talking about things where he’s start in the middle and work out.

Unstructured!

Roger: I met him again when we were doing Machine Gun Etiquette [with The Damned] at Wessex Studio and The Clash was recording London’s Calling next door. Guy Stevens was producing the Clash; he, of course, had done the famous Huey ‘Piano’ Smith album with the Bruegel painting on the cover on Sue records.

One day, Guy comes in while I’m in the middle of the mix. I handed him an envelope with the new Ace issue of our Huey ‘Piano’ Smith LP in it, and we’d put on the back, ‘Dedicated to Guy Stevens’.

I mixed the track and we finished, then I turned around to ask him what he thought. And he’s sitting there looking at the back of the record with tears streaming down his face.