In a parallel universe, Peter Quicke wouldn’t be putting out records – he’d be making cheese.

2017 marks the Ninja Tune MD’s 25th year at his hugely respected independent label.

In that time he’s overseen its impressive growth from a business which only employed its three shareholders (including co-founders Matt Black and Jonathan More – aka Coldcut) to a global operation with around 60 staff plus offices in Los Angeles, Montreal and elsewhere.

Back in Quicke’s youth, he could be found helping out on his parent’s dairy farm in Devon – where he’d assist with manufacturing cheeses and ice-creams, as well as getting his first taste of distribution, sales and marketing.

(Peter’s sister, Mary Quicke MBE, stuck with the family business – and is now a multi-award-winning cheesemaker.)

“Cheese is lovely to make,” comments Quicke. “It’s quite soulful in a way. And it just sits there…”

Artists, of course, do not just sit there; they have hopes, dreams and ambitions of ‘making it’ – just like the labels they sign to.

Artists, of course, do not just sit there; they have hopes, dreams and ambitions of ‘making it’ – just like the labels they sign to.

For a while in Ninja Tune’s early days, Quicke and his team settled for being a ‘tastemaker’ label loved by a tight-knit group of aficionados.

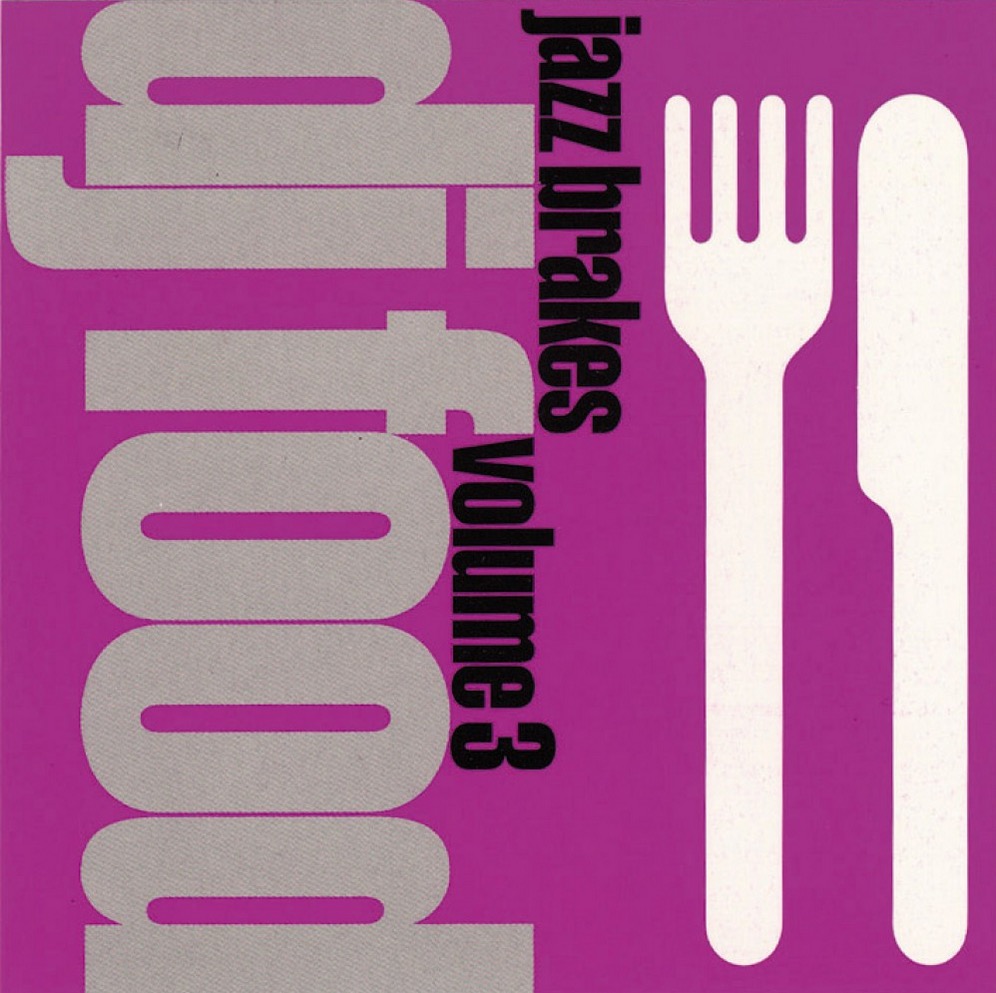

Classic records from the likes of DJ Food, Funki Porcini and The Herbaliser cemented Ninja Tune’s reputation as a highly influential label, and remain revered by jazz/hip-hop/breaks-heads to this day.

But after the landmark 1995 release of DJ Food’s Recipe for Disaster, Ninja started rolling out big record after big record – from the likes of The Cinematic Orchestra, Amon Tobin, Kelis and Mr Scruff.

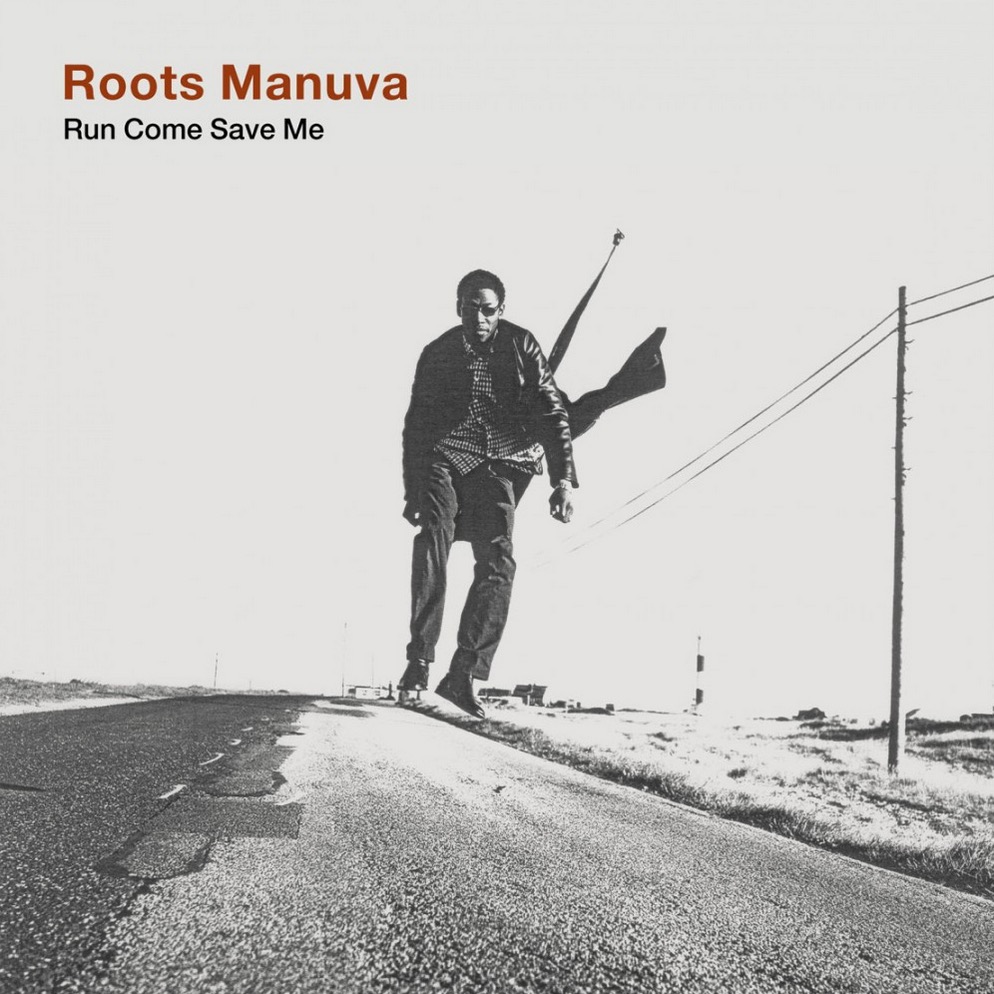

Other signings over the years have included The Heavy, Fink, Lou Rhodes, Kate Tempest and Roots Manuva, while two of the company’s artists – Young Fathers and Speech Debelle (on Big Dada) – have collected Mercury Music prizes.

Quicke has played a key a role in all of these records, as well as expanding Ninja Tune into publishing (with Just Isn’t Music) plus launching Ninja Tune label imprints such as Big Dada and Counter Records and working with Brainfeeder (Flying Lotus’ label).

[PIAS]’s Kenny Gates caught up with Quicke to ask him all about his life in music, the rise of Ninja Tune and what the future holds for his much-loved independent company…

Did you always love music?

Did you always love music?

I always bought records from when I was young. I was mad into Yes and Pink Floyd, things like that. Then punk came along. I was 14 or 15, and that was The Stranglers and The Clash, then Gang of Four – that kind of post-punk thing.

I bought a slightly crap mobile disco from my brother-in-law, two turntables with some speakers, amps and oil wheels. Me and a friend of mine used to go around and DJ. There wasn’t much of an alternative music scene in rural Devon back then, so we were playing a mixture of disco, boogie, soul and bits of hip-hop and punk.

Then you went to Manchester…

Yes. I was member 423 of the Hacienda. Joy Division were around by then. I saw Nick Cave, Madonna, New Order, Grandmaster Flash. Then I moved to London and was into all sorts of things – bits of rave, house, bits of psycho-billy… I had all kinds of jobs: I worked delivering sawdust, I drove one of those vans with advertising down the side. Then I worked in an Our Price for about eight months, after which I decided to go and work for my family.

So how does a man from a cheese-making family end up running Ninja Tune?

So how does a man from a cheese-making family end up running Ninja Tune?

I started hating the cheese and ice-cream. There were good bits to it, but I was mostly working on my own and the ice cream kept melting! I left, and I knew I was going to do something with music but I didn’t know what.

Then through a friend of a friend I got introduced to Coldcut (pictured), and their label manager had left the day before. They were wondering whether or not to continue with the record label, so I joined them in September 1992. They didn’t pay me anything initially, then we started to make a bit of money, so I got a share of that. After a year or so, I put a little bit of money in and we became equal partners.

What did your parents say?

My mother didn’t think I should work on the farm. She thought I should get away; she was supportive.

My father was ambivalent. They didn’t try to stop me. I’m the fifth of six children. They already had a few working on the farm!

What was the first release on Ninja Tune when you joined?

What was the first release on Ninja Tune when you joined?

The first release on Ninja Tune before I started was Bogus Order.

When I started they’d just released Jazz Breaks Volume 3 by DJ Food, which was Matt and Jon, which was Coldcut, which was… most of the artists on Ninja Tune!

Is it right they were trying to escape a Big Life contract?

Exactly. They couldn’t release anything as Coldcut – that had to go through Big Life, until the deal was signed over to Arista/BMG.

The first record I actually worked on was Steinski’s It’s Up To You, which was a protest record about the first Gulf War. And then I worked on Autumn Leaves by Coldcut. Arista/BMG gave us an exclusion to do vinyl copies, we sold around 5,000 copies of that which was fantastic.

What was amazing was that [Matt & Jon] said: ‘You can do some A&R.’ So I signed DJ Toolz, which was beats and breaks, and he went on to become the London Funk All-Stars, which was one of those sample-based things we did in the early days. Then I signed 9 Lazy 9 and out of that came Funki Porcini.

Was there a moment where you thought: we’ve got a real record label here!

Was there a moment where you thought: we’ve got a real record label here!

I was just so excited about the whole thing. I loved every minute of it – doing the MCPS forms, faxing the order to the manufacturer, going to look at the test pressings, it was all incredible. But it wasn’t going crazy, and we put out all sorts of strange stuff too.

So I decided, together with Matt and Jon, to separate the label into Ninja Tune and Ninja Tone; Ninja Tune would be the jazz/hip-hop/beats and Ninja Tone would be ambient and techno. At that point we released a 9-Lazy-9 album, a DJ Food album and a Herbaliser album, and our first compilation. And then, slightly in Mo Wax’s slipstream, Ninja Tune became a very exciting thing that everyone seemed to be talking about.

Ninja Tune, Matt and Jon, seems to always tussle between being commercial and being very underground…

That’s definitely how they are. They love some pop songs and classic soul songs, but they’re also really into underground stuff like Terry Riley, all sorts of hip hop, techno, reggae, classical… Matt loves music of course, but he sort of sees it as software, and so he’s always looking at it in a slightly different way; Jon’s very much a passionate collector DJ type person.

Coldcut was expected to have hits. Did they create Ninja Tune to do… not the hits?

Coldcut was expected to have hits. Did they create Ninja Tune to do… not the hits?

Exactly. Matt and Jon didn’t want to make another record like their first album ‘What’s That Noise?’. I wasn’t interested in making pop music. Most of the industry seemed to be repugnant to me at that point.

I definitely wanted to make music that was new, different and interesting. We didn’t want to compete with getting music onto the chart. We just wanted to put out music that DJs were into.

Do you analyse your signings?

Do you analyse your signings?

Now we’re a bigger label we do analyse a bit more than we used to. But a lot of it is still just on gut.

For Ninja Tune and Big Dada, it’s really all about whether it feels right for the label. But when we’re signing on Counter, we’re looking more at the artist – are they up for making lots of music and doing lots of shows?

Counter is perhaps what Ninja Tune would have been had we taken a different route with it. We decided in 2008 or so that Ninja Tune had become a bit amorphous musically, with artists like Fink and Andreya Triana (pictured) signed to it. We wanted to take it back to its more experimental, electronic roots.

But being a big label – there’s nearly 60 people here now – you do have to think about signing some records that will sell. So you become driven by the monster you make to a degree. It would be negative to stop and think: ‘Actually, we’ll just be a bit smaller’ so we keep growing.

The only way is up, as Yazz would have said!

What do you think of that [quandary] as an independent business person?

It’s always the dilemma for an independent. You climb up the mountain, with the survival instinct telling you that you have to grow, and then you look down and think: ‘My God, I’m so high I can’t go down now – I’ve got to keep climbing.’

Going down might mean going bust! That’s what used to frighten me from around 2002 to 2008. I spent most of the time terrified about going bust. We had about 15 people, and having to pay their salaries meant we had to keep putting out records, and we had to keep having faith.

The history of independent labels shows it’s half about always growing, and half about near-death experiences!

Yes, and also you’re driven by putting out music you really love. Those are the best bits; that’s what makes you think: ‘This is why I’m doing this.’

So how do you survive the moments of despair?

You sometimes think: ‘Oh f*ck. How are we going to get through this?’ Then again, you don’t really think like that when things are going really badly – you’re too busy sorting problems out.

The royalty period’s used to be stressful; in a way, you’re a bank. You collect money from sales and you have to pay it on to your artist. And if you don’t pay your artists, you’re nothing – you’re not a proper record label. Artists want to be with you if you’re honest and look after them.

What have been the defining moments in ensuring Ninja Tune’s success, cash-flow and survival?

What have been the defining moments in ensuring Ninja Tune’s success, cash-flow and survival?

There have been lots of them, but we haven’t had a Franz Ferdinand moment where it went crazy. That first bump in 1995 when the first Ninja Tune compilation came out, DJ Food’s Recipe for Disaster – we suddenly went up a level and it felt easy for a moment.

Then we went on with Amon Tobin and the Coldcut album and that worked okay. Then there was a bit when we were successful in America with Amon Tobin and Kid Koala – that was a bump.

And then Roots Manuva, Run Come Save Me and the first two Mr. Scruff albums – that was a moment that felt like it was working. More recently, it’s been about Bonobo, Odesza and The Heavy, as well as The Cinematic Orchestra.

Do you feel you have a close relationship with your artists?

Yes. Hanging out and talking to artists is a natural part of this. I probably don’t do enough of it, but that’s always the most rewarding bit of this job.

Your artists are very loyal to Ninja?

Your artists are very loyal to Ninja?

Most people don’t leave us, that’s true. I think that’s because we always try to find a way to do what an artist wants to. We spend quite a lot of money on tour support. We do our royalty accounting down to beneficiary level. It sounds like a small thing but apparently some other record labels don’t do it.

And it’s also a 50/50 deal here. Artist’s definitely feel like we’re on the same side – it’s not the label’s record and you’re only getting a small part of it, all the income and costs are equally shared. I think that engenders loyalty.

I read about Matt coining the term ‘co-operative capitalism’.

Yes, well that 50/50 deal encapsulates that. It’s a co-operation. We’re not trying to exploit artists. I think most independent labels feel they’re in some kind of co-operative capitalism.

What’s the difference today between an independent and a major?

It’s quite simple: we do it for music, and they do it for money.

Obviously indies have to have money to operate and majors put out lots of great records. But at root, what drives a major towards anything they sign is how much money they’re going to make out of it.

But you’ve got 60 people to pay for!

Yes, absolutely – but at the same time there’s lots of things we just wouldn’t sign, even if we knew they would sell really well. Because they don’t suit us and we’re not the right home. At root, it’s about music.

Obviously we have to make commercial decisions, but we have to be into the music to start with.

What’s the definition of selling out?

It’s how you feel about it. The Cinematic Orchestra are an amazing band and all of their albums are brilliant. But their tune To Build A Home, there was no intention for that to be a million-selling, million-syncing tune – it felt right when they made it, to them and to us, so that could look like selling out but it isn’t!

Are your ambitions somehow restricted by your refusal to go to the mainstream?

Are your ambitions somehow restricted by your refusal to go to the mainstream?

No. Our ambitions are as much about wanting to put out great records as about wanting to make money. We don’t see the purpose or end point of our ambitions being wealth. We see the end point of feeling like Ninja Tune has grown and the catalogue is something you’re ever more proud of.

Is that your fire? Pride?

Yes – pride in what the label stands for and pride in the group of artists we’ve worked with. That’s what makes me want to do it. We all need money to live, but it’s not the most important thing.

Do you believe if you do things with integrity money follows?

I think that integrity is definitely part of it. You also have to just keep working. Tenacity and integrity; they’re the key ingredients. Plus a bit of luck, passion, instinct and taste.

Do you have any mentors? People you look up to?

Do you have any mentors? People you look up to?

Matt and Jon were obviously mentors.

Then Mo Wax – I loved the first 20 releases with them. That was an inspirational time. Ollie Buckwell from Dorado [now at INgrooves], I used to ask him questions all the time.

And obviously labels like Domino, Warp and Beggars have made a huge impact and given advice freely. Even record labels like Atlantic – the original Atlantic – was just fantastic.

You release thoughtful music rooted in the subculture. What you think of the closure of Fabric, and ratings showing the declining London nightlife?

It’s disastrous. A ridiculous, small-minded, short-sighted mess. It’s crazy that Islington Council have such control over part of our cultural heritage.

Having said that, people have been talking about this for years. There’s always live music going on. But there’s such an opportunity to have more. In Montreal, they’re a much smaller place but they have almost as many gigs going on as London.

Could London lose its status as a home of live music culture?

That’s the terrifying thing. I feel confident there’ll still be great gigs and clubs in London. There’s so much energy here for it that people will find a way to do it.

In 1999, US radio banned DJ Vadim’s Your Revolution. How did you react?

In 1999, US radio banned DJ Vadim’s Your Revolution. How did you react?

We were delighted! It was the ridiculousness of it; there’s so much appalling, immoral, sexist music on US radio and yet this tune, which is actually a protest tune about sexism, got banned.

It was hilarious more than anything. We probably should have been very angry about it, but it wasn’t as if we were going to spend $200,000 getting it away on commercial US radio so it was just very funny – and some nice free publicity.

Do you feel part of an independent community?

Yes. Kevin at Warp and John Dyer are two of my favourite people in the music business. They’re down-to-earth, clever people. Why are you doing this interview? This is itself part of community building.

Is that community important to you?

Is that community important to you?

Yes. It felt terrible when Mute sold to EMI. Even Ministry [selling to Sony], who are a million miles away from what we are – it’s a shame.

Did you ever have conversations about selling yourselves?

Nah. We had a couple of people [enquire]. It just wouldn’t make sense. I don’t know what I’d do afterwards. I’d have to start again, so why would I do it?

Is this a job for you or a hobby?

A hobby, completely.

A well-paid hobby?

Well, not that well paid for years and years! It’s alright now.

What would the Peter Quicke of 1992 think of the Peter Quicke and the Ninja Tune of today?

I genuinely don’t think it would make any sense to me.

In a way, I’d just think: ‘YEEEAAAAH! I managed to keep it going for 25 years.’

Streaming. What’s your view as we stand today?

Streaming. What’s your view as we stand today?

It’s inevitable. At the moment we sort of rely on it – Spotify is our biggest revenue source. Would it be better if streaming never existed and we carried on selling vinyl and CD? I don’t know.

In a way, the reverence for the artifact is tied up with the emotions of the music. Streaming is gradually breaking that down – people’s relationship with music is possibly becoming more incidental and less involved and emotional. But on the other hand, it makes it possible for people to listen to music all the time.

Did Spotify save the business?

In a way, yes. They feel like an honest broker paying a fair royalty. But the other thing they’re doing is making the long-tail thinner and probably making the pool of music that gets listened to thinner.

That’s not a good thing. It’s the tyranny of choice. People don’t know what to listen to so they listen to the Spotify playlists. From our point of view it’s fine [with a large catalogue], although we’re always learning what works and what you have to be careful of. Whether culturally it’s good long-term is an interesting debate.

If you were to start a label today in a business that looks like it’s going to become 90% streaming in the near future, would you worry?

If you were to start a label today in a business that looks like it’s going to become 90% streaming in the near future, would you worry?

It probably is harder now. But when I started doing this, for years I worked all day and all night, and it was f*cking hard. Nobody wanted to review our records. There were a few fans, but nobody cared. We sold 2,000 or 3,000 at best.

It’s hard whenever you start a record label. In a way it’s easier now because you don’t have to spend loads of time fretting over manufacturing. Starting a label at any time in history is just shit-tonnes of work for years.

I remember so many times putting out a record and thinking, ‘This is brilliant.’ And then no f*cker out there would give a f*ck! There’d be a few reviews, it would sell nothing, and you’d just think: ‘Oh yeah. Of course.’ You can’t be depressed about that. You’ve got to carry on and put out great records for the sake of putting out great records.

You sound tenacious!

Tenacious and optimistic. You need both.

Romantic?

Ha! Maybe! Listening to music is a wonderful thing.

You’ve done very well with syncs.

It was Mr Scruff that really kicked it off for us – Get A Move On. People started saying to us: ‘You should send us your music for syncs.’ And then they started asking to put our tracks in this, that and the other.

It became apparent that our sort of music was good for that. And then Amon Tobin became a full-on sync hit. It became possible to put on proper campaigns for records that didn’t really sell very much, if you were tenacious with sending music to synch people, you could make it work.

Do you get frustrated when an artist refuses a commercial?

No. If an artist doesn’t want to be seen as the tune of Kellogg’s or something, that’s totally fair enough. And as a label we’re not tarnished: we wouldn’t be the label of Kellogg’s, but they might become the artist of Kellogg’s. So we totally respect that.

What has been the most extraordinary moment in your career?

What has been the most extraordinary moment in your career?

When we first heard the Diabolus 12″ from Cinematic Orchestra (pictured) and put it out. It felt like an unusual record, and everyone was very excited.

People would ring up and say: ‘My God, what kind of music is this?’ Up to that point the circle of trust in the jazz community, if you like, thought we were just playing at it. That changed things. And then obviously winning the Mercury Music Prize with Speech and Young Fathers was fantastic.

Tell us about a classic mistake you’ve made that you learned from.

Oh, Kenny! There’s so many and they’re all appalling. What keeps me awake at night: ‘I could have signed that person. Shit!’

There are a couple I know we could have signed. And I thought ‘let’s not do that because we have an artist a bit like that’. And then they turned out to release a masterpiece and you just think… f*ck. There are a few of those.

Also licensing deals to other labels in other territories where you feel like they’ve taken more from it than they should. We’ve done that before. I think Beggars have said they’ll never license again. There are upsides, but I understand that.

I went to see Richard Russell once about A&R. We had a great conversation, but the main thing he told me was just put out less records and focus on them more. Of course, to some extent he’s right.

We’ve hired more people so there’s enough time for them to really work on our really important records. But, then again, we keep putting out more and more records because there seems to be more and more great music out there…