Jeff Barrett – yes, that’s him behind the vinyl sleeve – could do with a bit of shut-eye.

When [PIAS]’s Kenny Gates catches up with the Heavenly Recordings co-founder, he’s fresh – or, tell the truth, not so fresh – from a ‘Heavenly Weekend in Hebden Bridge’; the first chapter of 2015’s 25-year celebration of his label.

The four-day anniversary event in Hebden, Yorkshire was headlined by modern day Heavenly stars including Cherry Ghost, Stealing Sheep and emerging Leeds singer/songwriter, Eaves.

The four-day anniversary event in Hebden, Yorkshire was headlined by modern day Heavenly stars including Cherry Ghost, Stealing Sheep and emerging Leeds singer/songwriter, Eaves.

These acts continue a wonderful legacy for Heavenly, which began in 1990 when Barrett was given the opportunity to launch a label by his friends at Revolver distribution.

Since its achingly indie beginnings, Heavenly’s been part of two major labels – EMI and Sony – and learnt plenty from the ups and downs of both experiences.

Today, the label is fully independent once again, fully run by Barrett with backing from [PIAS].

Heavenly’s roster has often touched on the sublime, ranging from acts such as Doves, The Magic Numbers, Edwyn Collins and Beth Orton to Mark Lanegan and modern-day indie superstars Temples (pictured above right).

Barrett and his label are also credited with ‘saving the Manic Street Preachers’ career’ – signing the Welsh agit-rock outfit for very early singles including Motown Junk.

Here, Kenny asks Jeff about the ethos behind Heavenly, his unorthodox path to becoming a label owner and why he’s still wrapped up in independent music, three decades after his career began.

Tell us more about a ‘Heavenly Weekend in Hebden’.

We went to a place called Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire to enjoy the first bit of celebration around our 25th year. We took over a venue [The Trades Club] and, to a degree, the town with all of our bands.

We went to a place called Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire to enjoy the first bit of celebration around our 25th year. We took over a venue [The Trades Club] and, to a degree, the town with all of our bands.

We’re London-based, but we’re not London-centric. Hebden has myth and legend about it; Ted Hughes the poet was born down the road, Sylvia Plath his wife was buried up on the moor. There’s also stories about the ridiculous number of lesbians and hippies up there, and even stories about a legacy of bad parenting meaning there’s lots of kids on smack. It’s nicknamed ‘Happy Valley’; it’s got a story.

I noticed the Trades Club appearing on my bands’ schedules and I went last year for the first time, and I loved it. I loved getting off the train in dusk in January and walking onto these cobbled streets and slipping on my arse. I loved the smell of the place, how it was described by a kid on my train; as the doors opened he inhaled and said: “You can tell you’re in Hebden by the smell of the gange.”

It was actually chimney smoke so someone’s ripping him off but, either way, I felt a vibe in that small town. And the atmosphere at the venue is fantastic.

Is it important for Heavenly to celebrate its life so far?

Well we definitely like to celebrate, given the excuse, and 25 years is as good an excuse as any. When we were 18 we threw a really big party on the Southbank in London – the Royal Festival Hall, The Queen Elizabeth Hall, the whole lot.

It was a real coming together of history – it was about everybody that had been on the label. It was a fantastic turnout: The Manics recorded seven songs for us [in the early ’90s], including two singles, and they came and played those songs.

It was a real coming together of history – it was about everybody that had been on the label. It was a fantastic turnout: The Manics recorded seven songs for us [in the early ’90s], including two singles, and they came and played those songs.

Beth Orton, who we had a fantastic relationship with but hadn’t worked with for some years, came and played. As a label bloke, that’s a really nice thing; having that lasting relationship with artists. They’re the important bit – their music is what makes everything memorable and valuable.

At that time, we’d been in this joint venture with EMI for six or seven years and that was just finishing. And as a result, my partnership with my long-term friend Martin Kelly – a big part of our story – came to an end.

Why did the partnership come to an end?

Well, money: there wasn’t any. There was a change of landscape in the industry and there was a change of landscape in our bank balance. We were at a point in our lives where for the first time we probably considered ourselves grown ups and that scared us.

“The reason our partnership came to an end at the end of the EMI years was money – there wasn’t any”

The EMI deal funded us very well; we were earning good money and we had good budgets. It ended when the industry was really changing – we realised that we’d enjoyed the comfort zone too much. Suddenly, when that was over, we weren’t really sure what we were going to do. Our primary concerns, of course, were out kids and our mortgages. It was a little bit scary.

We knew we didn’t want to go back to a major company and we knew that a major company would probably never want to go with us again. Not that [PIAS] isn’t a major company in its own right.

No, no – please don’t call us a major!

Okay, I won’t! But you know what I mean. You weren’t even on the horizon then, so we ended up doing the deal with Co-Op. There just wasn’t any money.

Heavenly Recordings couldn’t afford to keep [both of us], simple as that, so we separated. Martin does Heavenly Films with his brother and the guys in St. Etienne, who he’s always managed. And they’re doing some really great stuff.

Before Heavenly, weren’t you a press office for Factory Records?

I was a press officer in London, and I worked with Factory from early ’88 to early ’92. The Happy Mondays hadn’t broken out yet and the Hacienda was still empty, so it was a hugely significant periods of Factory’s history.

The Factory Records story is such a thrill. During those four years, the Hacienda went from tumbleweed to being the most important club in the world to closure. The Happy Mondays went from being a group to which a lot of people would refuse to do support gigs with, to being one of the most culturally important British acts of all time.

[video_youtube id=”bcn4UG6Jd0s”]

Did Factory give you the inspiration to begin a label?

No, I’d put some records out before then. I was Creation Records’ first employee in 1985. I fell into press by accident. I didn’t even know it was a job.

In 1983 I was the singles buyer at an HMV shop in Plymouth, Devon and I used to buy the independent stuff from a company called Revolver in Bristol. We were the go-to shop in the entire West Country for independent music.

And that’s where you met Mike Chadwick?

I did. Mike was still the Revolver shop manager then. Revolver had this brilliant, very independent shop its was heavy on reggae and into electro when that was coming in.

After selling far more independent records than any of the shops they were dealing with, I got a call from Lloyd [Harris, Revolver distributor] saying that Mike was going into distribution, and they were looking for a shop manager. I got the job. Back then it was all in one building; distribution was in the back room of the shop.

I’ve obviously always loved music, but I was also always kind of interested in how independent labels operated. Anything written on a record sleeve interested me, to be honest.

“I didn’t have a passport – I was 23 years old – and Alan [McGee] hadn’t explained what a tour manager actually did. I guess he didn’t expect me to come back without receipts, either”

I couldn’t believe the job: I was managing this fantastic record shop with this incredible amount of action going on in the back room; The Smiths debut was coming out, Aztec Camera’s debut was coming out. Mike and I became good friends. After a year there, I went down to Plymouth and starting putting on bands.

When I put on The Jesus & Mary Chain, Alan McGee came down to the gig. I remember being stood on the street outside the venue, and he said to me: ‘Barrett. What the fuck are you doing in Plymouth?’ That’s when he offered me a job on his label.

And so began your time at Creation…

I loved that label. Upside Down by the Mary Chain [1984] was only just out. When I was at Revolver we’d get all these white labels through and these sales notes, and I’d laugh because they were fucking bonkers – McGee (pictured) trying to explain tour dates and release dates etc. They were just punk rock rants.

I loved that label. Upside Down by the Mary Chain [1984] was only just out. When I was at Revolver we’d get all these white labels through and these sales notes, and I’d laugh because they were fucking bonkers – McGee (pictured) trying to explain tour dates and release dates etc. They were just punk rock rants.

So when I went to Plymouth [after Revolver], I rung him up and said I liked his label and wanted to book some of his bands in Plymouth. He said: ‘Are you taking the fucking piss mate?’

I said no, and asked why he thought I was: ‘Because I put my groups on in London and no cunt comes along. You think they’ll come and see them in fucking Plymouth?’

I said: ‘Shall we give it a go?’ And he said: ‘Aye. I like your spirit, man.’

He sent me a load of fanzines and flexi-discs – an indie kid’s wet dream.

What was your job at Creation?

Kind of a dogsbody, really. We’d take records to NME and Radio 1, take records to the cutting room – I didn’t even know what a cutting room was.

The daftest thing was that Autumn [1985] Alan asked me to tour manage The Mary Chain across Europe. I didn’t have a passport – I was 23 years old – and Alan didn’t explain what a tour manager actually was. I guess he didn’t expect me to come back without receipts either…

By the time we hit Holland, Benelux and Germany, I realised nobody had made the promoters aware that the Mary Chain played 15 minutes tops. So it was a struggle to even get paid at some of those gigs.

‘We’re not fucking paying you, get back on.’ And I’d say: ‘You just witnessed the best 15 minutes of your fucking life – the greatest rock and roll band in the world.’ It was a fucking debacle, really. But I saw my favourite group every night of the week and drank their rider.

How did your career progress from there?

A lot of the bands, including Primal Scream, couldn’t get agents. So I started doing that, putting groups on myself. And because I’d been an avid reader of the music press all my life and I knew what the writers on these music papers were into, I could target them with certain records. It worked and I got kind of good at it.

“When Tony Wilson turned up, he told us what he’d been doing with his day, smoked a huge joint then disappeared”

One day, a guy called Dave Harper who was doing press for Factory came down to me, knowing I was a huge Happy Mondays fan. He told me I was leaving and did I want to do press for Factory. I went there and met Alan Erasmus [Co-Founder] and Tina Simmons [GM], then waited three hours for Tony fucking Wilson to turn up!

When he did he told us all about what he’d been doing all day, smoked a huge joint then disappeared. It was the most unorthodox interview I’ve ever had – not that I’ve had many interviews. Suddenly I was a press guy for Factory but kept doing a bit of work for Creation.

What would be your proudest moment in your career, and what would be your lowest moment?

Honestly, the proudest is getting to 25 years with Heavenly and marking it with such great groups in Hebden. We’re at 25 with a really fucking great roster of artists.

Honestly, the proudest is getting to 25 years with Heavenly and marking it with such great groups in Hebden. We’re at 25 with a really fucking great roster of artists.

I’m also proud that after the [post EMI] bump, which is probably the most miserable period – breaking up with Martin wasn’t nice – we were able to rebuild, with the support of Danny Mitchell especially. That’s both the shittiest bit and the best bit.

How did Heavenly come to be in the first place?

Mike Chadwick started Heavenly, really; he called me one day and said he wanted to start an in-house label [at Revolver] and for me to do the A&R. I was high one night and Heavenly seemed appropriate.

“Mike Chadwick called me and said he wanted to start an in-house label with me doing the A&R. I was high one night so ‘Heavenly’ seemed appropriate”

The first low came quite soon after, when Mike decided that Heavenly had already become too big for what he’d envisaged and didn’t want to fund it to the tune that I was hoping he would.

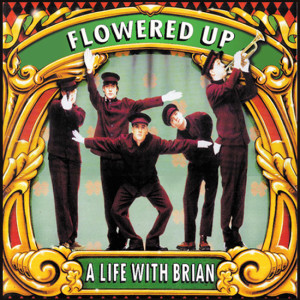

The first signings were from St. Etienne and a group from North London called Flowered Up; as a publicist I put the word out that they were London’s answer to The Happy Mondays, which seemed to work. And then I signed the Manics. These things needed a video, a poster, some advertising – but that’s expensive.

Where did you take Heavenly after you parted ways with Revolver?

Well I was like: ‘Fuck! I was enjoying that! Now what do I do?’ That was when I fell into the clutches of the majors. I’d never thought about major labels before; I wasn’t keen to get ‘into the industry’ as such.

But this guy Rob Stringer was around, he’d signed the Manics [for Columbia] – they only had a singles deal with me so it was no problem.

London Records made me this offer, then Rob. I just wanted to be able to keep putting out records. I went with Rob and had two years [at Sony]. I didn’t know what I was doing, and they didn’t know what to do with me. When we came out of that, I thought we’d be independent again.

But Deconstruction, who were part of RCA at that time, were a a really successful dance music singles label and wanted to broaden their remit into making albums, so they made us an offer and we went in there. I had my fingers in a lot of pies at the time, hanging out with acid house guys and running a club night with the Chemical Brothers.

Heavenly’s roster today is more rock and indie than dance.

Well I’m 52 years old and I don’t spend as much time in the clubs as I used to! There was a time when I would take test pressings or acetates from The Happy Mondays and put them straight into the hands of DJs – Andrew Weatherall, Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling – and get them played then and there. I did ‘sort of A&R’ on Screamadelica through that; I introduced Primal Scream to Andrew Weatherall.

You do have your own bar though.

Yeah, The Social in London, which punches above its weight. That was 15 years old last year. And our club night that spawned it was 20.

Man, you know what it’s like, you’ve been around long enough and suddenly you’re celebrating shit all the time.

The tagline of Heavenly is: ‘Believe in magic’. After 25 years, do you still believe?

Yeah! Absolutely. I saw it happen in Hebden. That [motto] is everything to do with The Lovin’ Spoonful, who had a song called, Do You Believe In Magic?

Yeah! Absolutely. I saw it happen in Hebden. That [motto] is everything to do with The Lovin’ Spoonful, who had a song called, Do You Believe In Magic?

“Do You Believe In Magic? by The Lovin’ Spoonful is, to me, the Holy Grail. It’s about the love of music, rock’n’roll and having a good time.”

The lyrics to that song, the emotion of it, are to me the holy grail – it’s about the love of music, of rock’n’roll and having a good time. That ticks all the boxes to me.

So do you see yourself as a hopeless romantic?

Completely. How can you not be?

That’s my favourite question. I’ve been told I’m one too.

Well, we’re the sort of people who love myths, legends, poetry. That’s who we are.

If you weren’t running a label, what would you be doing?

I’d still be working in a record store. All I ever wanted to do as a kid was work in a record shop. It took me four to five years to get that job and I loved it.

2015 looks exciting for Heavenly: your new act Eaves played at the [PIAS] conference in January and was fantastic. Now you have Temples on the second album – they have a really good chance of becoming very significant.

On a serious, professional tip – rather than just banging on about magic all the time – one of the things I’m most looking forward to this year is working with Temples on that record. They made a fantastic debut and the world seems to want the second record.

They’re seriously talented guys. James, the guitarist/songwriter/producer, has a real vision. I like being around that boy.

Equally, working with Stealing Sheep is great. On their first album, I’d have never immediately guessed they’d have moved from this willingly weird folk to become this kind of technicolour groove outfit. And Joe, who is Eaves, is a brilliant talent.

[video_youtube id=”Sw_qvDx4xMI”]

What are your memories of the explosion of Doves?

There’s a lot of significance around that on many levels. We were aware of Doves; Martin Kelly knew Jez, and the word was they’d made a record. We bought this EP, Cedar Room, and it was on Rob’s Records; Rob being Rob Gretton who I still miss every day.

Rob was a very good bloke and I learnt a lot from him; he was a musician’s friend. He was excellent with artists – especially broke ones. With Doves, Rob incredibly sadly and prematurely passed away just as Doves had finished their debut album.

“Doves were the first thing we brought into EMI. Suddenly I had the attention of everyone in that building who didn’t get much of a thrill from working with Geri Halliwell.”

We waited for an appropriate period of mourning, then approached Rob’s widow, Lesley, and asked if we could talk to the group. There’d been other interest in the group – some others didn’t show quite the decorum we did [after Rob’s death] – but when we want something we don’t mess around or let anyone else get a look in, really.

We loved Doves. That debut LP is a masterpiece. It didn’t surprise me they did so well. It surprised some other people, for shit, stupid reasons.

Can you be more specific?

One thing was I had people idiotically saying: ‘He can’t sing.’ It was like: ‘Really?! Of course he can!’

The other thing about Doves was we’d just done our deal with EMI and they were the first thing we’d brought in. We had a deal with this label that was having success with Robbie Williams and was trying to have success with Geri Halliwell.

I mean, man, we brought one of the most exciting rock bands in the world! Suddenly I had the attention of everyone in that building who didn’t get much of a thrill from working with Robbie Williams or Geri Halliwell.

[video_youtube id=”4z7CELN-eLw”]

What was it like working within a major label generally?

I can speak honestly and fondly about the time we had at EMI, our last period of working within a major. But the thing that people need to remember about us then was we weren’t a ’boutique’ label, whatever the fuck that means. We had our own office and our office was basically a nightclub. We were still fighting the indie wars with EMI, even when we were part of them.

For instance when we found The Magic Numbers, we knew we’d found this great group. Imagine if we’d done that completely independently – fuck! We sold over a million records on that first album.

They didn’t get it. I remember having this argument: “At the one end you’ve got Pete Doherty’s junkie business going on, but this is like a ray of sunshine. There’s room for both!” We put together this offer…

How much money was it?

It was for about £8,000 for a mini-album. And EMI said no! I was second-guessed. I told them: ‘Don’t fucking second-guess me.” I rarely had to end up throw my toys out the cot but I did.

Thankfully, one of the guys there did go: ‘Alright, alright.’ They weren’t asking the right questions of the group. They thought they were that dreadful word, ‘retro’.

Then [Sony boss] Rob Stringer got involved, and before you know it it’s a £125,000 [deal] rather than the £8,000 – then potentially £40,000 we would have paid.

That was one moment where our instinct and attitude clashed with a major.

What about signing the Manics so early on? What are your memories of that?

A lot of people didn’t get that because they thought we were a fucking dance label! But as we know, music is music.

I thought they were the best thing around, loved them; they were bright, gobby, weren’t afraid to speak their minds, lovely people and incredibly committed.

Do you feel part of an independent music business community today?

Yeah, I think so. We’re a passionate bunch – we give a shit.

“We’re a passionate bunch. We give a shit.”

We’ve been very lucky to meet Jason Rackham along the way. He’s been incredibly supportive of our business.

I’ve heard that you refuse to compete with others in our world for acts.

Well it’s good manners, isn’t it.

Business is not often about good manners!

Well then maybe I’m more about good manners than I am business. I think if another guy or girl gets to an act first, fucking pay them some respect.

It’s the same with [Rough Trade’s] Geoff Travis and Jeannette Lee or [Wichita’s] Dick Green and Mark Bowen; I let the manager of [a given act] know that if it goes tits up with those guys that I’m here, but I ain’t gonna go in there and chuck another £10k to see what happens.

Why would I do that to people I respect? We’ve all got to make a living – why make it harder for each other?