The music business should probably be thankful that Terry McBride is slow at making coffee.

The Canadian co-founder of Nettwerk was a promising civil engineering student in the early ‘80s when he decided to take a sabbatical and, with the help of co-founder Mark Jowett, set up his own label in Vancouver.

To get the venture off the ground, McBride worked as a pizza delivery boy, record store clerk, lifeguard, in a fish factory and even as hot drinks server – a position for which he was wholly unsuited.

“I was a barista for a day,” he tells [PIAS]’s Kenny Gates. “I got fired for not being quick enough.

“The record company was what we did when we got up, at lunchtimes and in the evenings – and throughout the weekend.”

Junior job roulette behind him, McBride officially opened Nettwerk’s doors in 1985, with the label having previously been used as a base to issue recordings of Jowett’s band, Moev.

Early Nettwerk successes included The Grapes Of Wrath and Skinny Puppy, before McBride signed teenage singer/songwriter Sarah McLachlan, offering her a five-album deal.

Each of McLaclan’s records enjoyed a warm reception and significantly grew her fanbase but – as is so often the case in indie world – it took patience and long-term belief before the big time came calling.

McLachlan’s fourth album, 1997’s Surfacing, was a huge international release, going Diamond (10Xs Platinum) in Canada and selling 8m copies in the US, as well as scooping two Grammys.

More major hits at the Nettwerk label have included The Barenaked Ladies (and global smash ‘One Week’), Dido, Passenger and Sum 41 – whilst it also released Parachutes by Coldplay in the US after the record was passed over by EMI.

Nettwerk’s skills haven’t stopped at recorded music, either: the business runs a respected management organisation, currently looking after the likes of Father John Misty and Mike Posner (‘I Took A Pill In Ibiza’).

It has also built up a valuable publishing catalogue – a big chunk of which it just sold to a capital fund managed by Kobalt Music Group.

Kenny Gates caught up with Terry to ask all about Nettwerk’s creation, his staunch opposition to punishing fans during the piracy era… and how to treat your artists and staff the right way.

So, it’s the mid-eighties. How do even you start a label out of Vancouver?

So, it’s the mid-eighties. How do even you start a label out of Vancouver?

Back then, the world was round – now it’s flat!

The only reason to start a label in Vancouver 30 years ago was because you didn’t know any better and it was where you lived, and contained the music scene you were in.

Would Nettwerk have grown differently or been better if it was in Toronto, LA or New York? Possibly, possibly not.

How did you get into starting a label when you were a student?

I was [studying] civil engineering at UBC [University Of British Columbia]. When I came to the age of 21 I had to make a decision: I’d done three years of University. Did I want to continue in civil engineering with the ultimate goal of becoming an architect – a seven year process?

My sport of choice at that time was field hockey; I played for the Canadian national team, and that was requiring 30 hours a week. So that was also an option.

But my passion was music.

I took a sabbatical from UBC, and stopped playing field hockey. I decided to take a year or two off, much to my parents’ fear, and start a record company with Mark.

We didn’t know anything, which was possibly our biggest gift – as we weren’t locked into any methods of how it was ‘supposed’ to be done.

Engineering teaches you a certain way of thinking. And what I saw lacking [in the music industry] was data; information. A lot of it was smoke and mirrors.

I got the intuitive, musical part. I understood loving artists and the emotional connection of it all, but I thought: ‘Where’s the data to prove this is actually happening?’

What was the first musical experience which blew your mind?

I was one of those kids with an AM/FM radio and some earbuds. It went from The Beatles to ‘70s rock stuff and then the beginning of my own musical journey – U2, early Joy Division…

I still remember going to University parties where they’d start playing Stairway To Heaven and I’d stick on I Will Follow.

They’d put up with my musical choice for one or two songs and then go back to their seventies rock stuff!

U2 back then were very cool. Now it’s perhaps not so much the case…

U2 back then were very cool. Now it’s perhaps not so much the case…

Back then there was nothing like them.

Then there was the whole early English movement: Depeche Mode, before they became commercial sounding, Cabaret Voltaire… all these things that was a sound which was not on radio.

I worked at the UBC student radio station and I had my own one-hour import show. I got really, really into music and kind of paused everything else. It’s still paused!

So you’re part of that independent school of labels that began in a back room. Did Nettwerk have any starting capital?

No. It started in my one-bedroom apartment, and the separation from where I lived to the office was the stacks of vinyl records, from floor to ceiling.

We had zero capital. I had $5,000 worth of Canadian savings bonds which acted as collateral at the bank. We had a loan of credit of maybe $10k, and we’d taken it, then pay it back, then take it, then pay it back.

Eventually the bank manager went: ‘Take a loan of $25k and stop paying it back – don’t feel like you need to.’ We were surviving by the skin of our teeth, which is why I had to chase money all the time.

I remember you chasing me for money!

I had to! That was the difference between us paying the rent and not!

The independent record business back then meant you couldn’t get paid for a product you gave to a store or distributor until they wanted more. We’d say: ‘You can’t have more until you pay us for what you’ve already sold!’ It was a matter of always, always chasing money.

Mark was in a band called Moev, who I saw at a house party. For some reason I persuaded them they needed a manager – and that I was a manager – when in fact I wasn’t; I knew nothing about it. But I definitely had more business acumen than they did.

A year in we realised no-one was going to sign the band so the only way to get their music out was to do it ourselves. That was the start of the record label.

Where does the name Nettwerk come from?

First it was called Noetics. That lasted for all of about 18 months and then we basically went bankrupt. The word ‘network’ is quite common now, but if you said it to someone back in 1984, they probably wouldn’t have known what it meant.

There were no computer networks then. So it was a very unique name, but because we’re fans of Kraftwerk, we decided to do the German version.

We decided that we were a singer/songwriter label, in that our artists wrote and performed their own music. That could be electronic, hard edge, soft edge, pop or folk music.

It wasn’t like some of today’s pop stars where the songs are written for them, and it’s produced in production houses.

There’s something special about being on the west coast. How did that influence the company?

Being in Canada on the west coast had a huge impact on where we went because to go across Canada, the next city driving-wise was 16 hours away. But I could drive across California in 16 hours, which has a bigger population than the whole of Canada.

So our logical market was the west coast of the US. We never viewed ourselves as a Canadian label. Our initial push was into the US college charts.

I don’t think we had a Canadian distribution deal until ’88 – four or five years in.

“Our logicial market was the west coast of the US.”

Vancouver is in a blue zone – it’s a city built in a rainforest. Probably one of the cleanest major cities in the world.

You can be at an ocean and swimming within five minutes outside the city centre. We still have an office here because the four owners of Nettwerk won’t move. This is where I want my kids to grow up.

There’s something special about this city, it’s probably the most accepting in the world to all cultures. It’s beautiful.

Was it difficult being from Canada and trying to break the US in the early days – did you have an inferiority complex that you’d be seen as somehow provincial?

Was it difficult being from Canada and trying to break the US in the early days – did you have an inferiority complex that you’d be seen as somehow provincial?

I never saw that in my dealing with Americans. Most of the music that we were releasing and were interested in was only really happening in six or seven cities in the world: Chicago with Wax Trax, Vancouver with Nettwerk, what you guys were doing in Belgium and Mute in London.

That was kind of it. It was about the music, not where you came from. In the early days, the first 10 years, probably half of our roster was international.

And if I look at it today, probably 70% of our roster is international.

Not being in Toronto meant we weren’t in the centre of the Canadian music business and we weren’t following the same rules as everyone else. There was no-one else in Vancouver – it was just us and a few other indies.

We were kind of on our own, which was a really good thing.

Did you have any inspirations?

The early graphics of 4AD. I loved the way they created a brand around the graphics even though the music releases could be quite different. That really affected us.

On the business side, personally, the only guy I would go to was a fellow named Roy Lott, who was Head Of Business Affairs and then Head Of EMI.

When I was having our first commercial success, having someone who could help you through and teach you how not to do it was really helpful. He helped me work out how to do deals right and how to play the radio game right.

What turning points were there in Nettwerk’s history? When did you go from running a ‘bedroom business’ to a ‘real business’?

It took a good ten years for Mark and I to take an income from the company that was more than if we were on the dole.

In the early years we had success with Grapes Of Wrath inside Canada, then Skinny Puppy in the US and Europe. With Sarah [McLachlan], the first and second records did okay, the third record did pretty good and the fourth record went absolutely nuclear.

Behind that came [star-studded McLachlan tour] Lilith Fair, the biggest travelling festival in North America. That took an artist who might work really hard to sell a million to one who could sell ten million units – and a million units in Canada alone. It changed the company.

[video_youtube id=”MlyzjfLF0xg”]

In which way?

All of a sudden we were well-financed to do a lot of other things You started to see the building out of a worldwide artist management company.

You had Avril Lavigne, Barenaked Ladies, Coldplay, Dido, Sum 41 – it was a huge list of hugely successful artists.

We had offices all-of-a-sudden in London, Hamburg, New York, Nashville, Boston and LA. The business got complicated!

There was a series of bumps, and with every bump things became bigger.

Then Napster came and everything flattened out…

Is the streaming business good for Nettwerk and independents?

Is the streaming business good for Nettwerk and independents?

I love streaming – it allows the middle class artist to come back. It allows the artist who before streaming could not sell enough of their records to actually stay at home and make a living. They had to tour.

There is too much touring and it took away from the creative process. In the ‘80s and ‘90s and even early 2000s, you could wait two or three albums for an artist to finally deliver on what you intuitively thought was their amazing talent.

When Napster stripped the whole catalogue business away, you had to make it on the first album. And the whole chemistry changed. We’re now back to a world where it’s not about that.

Nettwerk’s whole philosophy – a baseball analogy – was to have base hits, artists that maybe generate $15,000 a year. That’s enough income that you could justify doing another album. If we got a home run, great, but our business was never dependent on having a home run.

Streaming is good for Nettwerk and [PIAS] because we have a catalogue. But if streaming was around in 1984, would the income on our new artists have been sufficient for us to survive?

The one thing about streaming that’s really interesting which didn’t exist in the physical model was you go to a flat world. We have the ability to see if an artist is getting traction in the Netherlands.

30 years ago, we didn’t have the ability to see that. It’s back to data. I know exactly what’s happening and exactly where it’s happening.

If we look at Passenger, it took 18 months to break Let Her Go. If we go to Mike Posner, [I Took A Pill In] Ibiza; that started in Finland and Shazamed in Russia. But it still took us 14 months to break it in the US – and he’s a US artist.

Without a flat streaming world, that song would never have become a hit, and neither would Passenger.

It all had to have a way to spread, and streaming enabled that. People like to share playlists – I’m hoping Apple will fix that because right now, Apple Music is 100% curated from inside the company, which is a huge disadvantage to their platform and a huge advantage to Spotify.

70% of the streaming of my artists [plays] are not on [first party] playlists – it’s coming from shared playlists. That’s a steady income for those artists.

What about streaming exclusives?

I don’t like them. You are forcing consumers to go to a place to listen to your music. Exclusives will do one thing: drive piracy.

Piracy was created through Napster due to the fact people couldn’t get what they wanted.

“Piracy was created due to the fact people couldn’t get what they want. Now [exclusives] are creating the exact same situation.”

Now you’re creating the exact same situation, and it’s purely based upon greed.

Telling the consumer where they have to go to listen to the music is the wrong approach and it’s disrespectful to fans. I respect artists that have done it, but it wouldn’t be what I would do.

Nettwerk is a publisher, record company and management company. You must have laughed when Sanctuary ‘invented’ the 360 model a few years ago…

Ha! I think what Sanctuary created was a pyramid, which spiralled all the way down…

We’ve been 360 for a long time and the only people who’ve done more than that is Disney, which is 720-degrees; they own friggin’ everything!

Nettwerk became a 360 company not by design, but by being pragmatic. We would put money in to create music, we’d release the artist’s album, then they’d sit in Vancouver and do nothing. If we didn’t book shows for them, they wouldn’t tour. If they didn’t tour, the chances of us selling records was a lot harder.

So we started booking them, and then a year or two in we realised we were doing artist management, and made it official. Each division was created through logic – we were already doing it, we just didn’t know what we were doing!

Being a manager and label must have its conflicts. If streaming becomes 90% of the recorded music income of the business, do you think there’s any validity in an artist having a record label?

Being a manager and label must have its conflicts. If streaming becomes 90% of the recorded music income of the business, do you think there’s any validity in an artist having a record label?

Yes, because if you’re a new artist and there’s so much noise out there.

Do you think that you can get enough traction alone? Maybe. But if you have three or four other people helping you get that traction through their relationships through curators of playlists, music supervisors or radio programmers, that helps you a lot.

“Nettwerk offers a very simple deal: 50/50 split of net profit.”

Nettwerk has a very simple deal: 50/50 of net profit. You can have 100% of 1, or 50% of 10. What do you want?

Certain artists want the former, and we’re just fans of them. But those who want the second one are better off because they’ve got a whole group of people with connections working passionately on their behalf. And guess what? I have to pay those people’s salaries.

But with your management hat on, couldn’t you suggest that a management company can do all of that?

I suppose, but managers traditionally make a 15%-20% commission.

That would never underwrite the cost of the infrastructure needed to get a baby band to the point where they would be successful.

You think that labels are still worthwhile for artists?

Absolutely. But they have to add value. If they don’t add value, don’t do it. If you have an artist who wants to be a pop act and be on radio, go sign to a major label.

If you want to be able to make a living creating the music you love with a team to market and promote it, sign to an indie.

An artist needs to be honest about what they want to be and who they want to be, and align themselves with those people.

Find partners that add value and share similar passions and thoughts about the world.

Surely you’ve had offers to buy into the Nettwerk label. You’ve never been tempted?

Never. I’ve even had offers to run major labels and I’ve turned them down.

Why did you turn them down?

I love working for myself and being my own boss. One major label situation I was offered 10-15 years ago would have meant me working with artists whose music I didn’t like. That wasn’t me.

It’s not that I wouldn’t have liked them as people, but what value can I offer to someone’s music if I don’t like the music?

It would have meant a very nice paycheque, but it’s not me. People follow their own paths, and at a certain point become comfortable with understanding their intuition.

“If you throw logic out the door and follow your intuition, you’ll do really well.”

If you throw logic out the door and follow your intuition – as an artist or a business owner – you’ll do really well.

For me, music is emotional. We’re in a business that monetizes emotions. Getting a letter from a fan because an artist’s music stopped them from committing suicide; that has more value for me than a cheque.

When I went into the yoga business, I soon realised it’s really the same business. Music and yoga are both thousands of years old, and they both deal with emotions. And they both make the world better.

Are you a romantic?

I don’t know… I follow my own passions. I don’t follow a rule-book. That’s why you and I have always gotten along really well.

Even amongst our ups and downs in a business relationship sense, we’ve always got along great. Same with Mark.

Because I think we’re nice people – not just because we’re Canadian!

Perhaps being independent and having a company ethos is partly about being a nice person. It is important for [PIAS] certainly to deal with fair people…

I know if we shake hands now, the deal is done. That’s so key.

We’d then give it to lawyers who’d mess it up and we’d have to get involved again, but from our point of view the deal is done.

There’s certain people in this business I can do that with and not think about it again.

Which of your business operations do you feel closest to?

I sit between label and management. I don’t want to manage artists but I want to help my management partners manage artists.

But I love the label. It’s just purely about the music. I don’t necessarily have to deal too much with the personality that makes the music.

What are your proudest moments?

Obviously breaking Sarah McLachlan was huge. Also breaking Coldplay on that first record when American radio had shut out British music.

Please explain: Coldplay’s an EMI band. What’s that got to do with Nettwerk?

Please explain: Coldplay’s an EMI band. What’s that got to do with Nettwerk?

The first Coldplay album was on Parlophone. Back in those days we were distributed within EMI in Canada and the US.

They had a process whereby international artists were either picked up by Virgin, Manhattan or Capitol [in the US] but if they weren’t picked up their records were never released.

The whole EMI family passed on Coldplay’s first [EP], and I called Roy Lott – the President of EMI – and asked if he’d mind if I phoned Tony [Wadsworth] to take the band on, because we loved the song.

Coldplay’s first record for the first six months was on the Nettwerk label in America. Then we lost it – as EMI had the ability to boot us out and pay us an override for getting it going.

“The whole EMI [US] family passed on coldplay’s first EP.”

It was a fellow called Tom Gates who took Yellow to radio and broke Coldplay. Tom is also known as the guy who found fun, signed Christina Perri and is one of the managers of Mike Posner. A musically brilliant person.

After we got booted and Capitol took over, Phil who was Coldplay’s manager at the time, phoned me up and said: “We’re having issues. We need you guys back in the mix. Would you mind coming in as co-manager?”

Then just before the second album came out, Phil got ill. He asked us to become worldwide manager, working with his assistant in London. We said yes, and Dave Holmes who worked for us within the label became full-time on Coldplay.

Then after that, on the third album, Dave left Nettwerk and took the band with him. Phil got better and I believe is back in the mix now.

Have you made any mistakes?

Of course. Sometimes you sign artists thinking you’re going to sell a lot of records and you don’t. That’s often the universe saying: ‘Get back to why you’re successful.’

You’ll turn around after that and sign some bluegrass band because you love the song. And ten years later, Wagon Wheel has sold 2m copies! Signing it because you love it is very different to signing it because you think you’re going to make money.

Any business mistakes?

Oh, probably signing distribution deals with major labels and the odd licensing deal here and there!

I don’t look at mistakes. I love the saying: on a rollercoaster you don’t scream on the way up, but on the way down. The fun part is the way down.

To me, every time you make a mistake it’s a great opportunity. In some of our early bands that we signed to major labels, we didn’t keep the rights. I learned to keep the rights.

Would I love the worldwide rights for Sarah McLachlan? Absolutely. Do I have them? No. I have a licensing deal.

That did not get in the way of Sarah’s career but it was not the best business move for Nettwerk.

YouTube. What’s going to happen?

YouTube. What’s going to happen?

I’m not a fan. There’s some really good things about YouTube, but some really bad things too. It’s a bit of a quagmire because you see some artists pull their music off streaming sites yet leave it up on YouTube. The irony of that is bizarre.

YouTube does not treat creative people and intellectual property with an awful lot of respect. Their whole ad-share thing has been driven by piracy. It’s unfortunate; their rev share model is not a fair model.

I’m not saying it has to be the Apple model or the Spotify model. But if YouTube’s model was the only one available in the music business, there would be no more music business. The Spotify, Deezer and Apples of this world treat the creative community a lot fairer.

You supported consumers a decade ago when the RIAA started suing fans for piracy…

I see no business logic in suing your customer. I also think that the music business as a whole saw it as a way of making money from their customer.

It was a litigious process which in itself is negative and destroys lives. Plus it was a horrible image.

A Sarah MacLachlan song was in one of these lawsuits. Sarah would never sue a fan – she doesn’t have that negative energy in her. That’s not who she is.

“The music industry was destroying its business and I couldn’t let it happen.”

They were using this song to sue this person, and I’d had enough. I told the RIAA: “You do not understand what a song is. A song is not a copyright. It’s not a lyric. It’s not a chorus. It’s not a chord sequence. It’s an emotion. And when someone connects with a song, they attach their own emotion to it.

“They own that song now. It’s a bookmark in their lives. How can you claim to own someone else’s emotion? You need to monetise the emotion – not sue it.”

I was the first member to step out and say “No, this is wrong.” I defended that position.

It cost me a fortune, but we were destroying our business and I couldn’t let it happen. I wrote a paper back in 2007 about the idea of a digital valet. That’s what Spotify is.

What do you mean by ‘digital valet’?

What do you mean by ‘digital valet’?

Something that would go find you the music you wanted. It’s your mum’s 50th wedding anniversary. “Go find me the top songs from that year.”

We needed to add value and experience to the music. Something akin to what the live industry has done. If you can sell water in a bottle while you can get it free from a tap, that’s because you’re adding an experience.

I said [the music business] needed to get there, and quickly – because what you don’t want is a dark cloud. You don’t want someone to build a cloud-based system which delivers an experience via piracy.

That’s why I’ve been a major champion of Spotify from the beginning – it’s a digital valet. I love Spotify because it’s so friggin’ easy to use and it gets me into music. It delivers the experience and the emotion.

Where do you see the market in 10 years?

95% streaming and 5% physical, which will be mostly vinyl, and mostly sold at live shows. Streaming is capturing the piracy market. It’s so much easier to use Spotify than to pirate now.

Would you say Spotify has saved the business?

Yes, absolutely. And for those artists who complain they’re getting nothing from it, look at the deals you have with your record labels. I know that all of the Nettwerk artists are happy with their Spotify royalties. Very happy.

Why did you recently sell your publishing catalogue to Kobalt’s fund?

Nettwerk on the publishing side had a dual strategy: organic growth and acquisition. When the cost to acquire became so great within the marketplace, it created an opportunity to actually sell. To basically utilise those funds towards future strategies.

Kobalt was the right partner to sell to. We needed to sell to someone who was a better publisher than ourselves and who would add value to all the writers that had come to Nettwerk.

We chose who we wanted to sell to, and then went through the process to get the right price. Now Nettwerk is debt-free, very well financed and investing quite heavily in intellectual property on the masters side.

You raised $10m for Nettwerk three years ago. What happened to the money?

That was so we could go acquire things. And then we sold our publishing catalogue… for more than what we raised!

What will become of independent labels like ours?

What will become of independent labels like ours?

Over the next five to ten years or so, Nettwerk will set up a royalty fund. Part of our income stream will sit in that royalty fund, allowing our shareholders to have some sort of liquidity.

The option [for a label owner] when you get to be 65 or 70 is: do you sell it to someone who throws away the legacy? I don’t want that to happen.

There are younger people within Nettwerk that could do a very good job adding value in the future, and I’d love that to be possible.

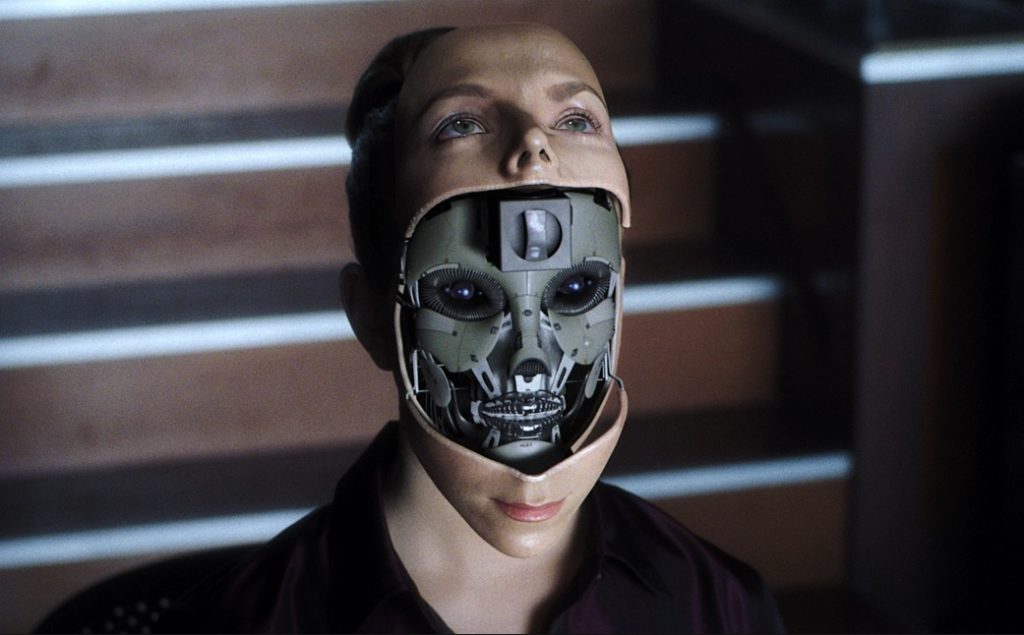

“That’s the biggest threat to the music business: Artificial intelligence.”

It’s a matter of creating a fiscal situation that allows liquidity for all partners, but also the ability for the company to continue as it is without having to be sold.

I’d like to setup something, where the passion and vision keep going. Because after streaming becomes the predominant force, I don’t foresee any future changes in the music business – it will all come down to how great you are.

AI [Artificial Intelligence] could screw that up…

What do you mean?

When we start having AI bands, that’s going to be really interesting.

That’s the biggest threat to the music business: AI’s ability to – at some point – encompass emotion.

You’re seeing elements of that within the gaming world now. And you’ll get it inside other forms of media too.